Because of their white ancestry, members of the Hemings family have been negotiating the color line ever since they left Monticello. Many of Sally Hemings’s descendants, in particular, have had to continually assert or defend or adjust their racial identity in a society that insisted on a simple division into black or white. The hardening of racial attitudes by the beginning of the twentieth century into the so-called “one drop” rule made the situation ever more difficult.

While Sally Hemings’s son Eston and his family determined to live as white people in the mid-nineteenth century, most of her son Madison’s descendants continued to identify themselves as black, even though their appearance was racially ambiguous. For generations, they found spouses whose light complexions and Caucasian features matched their own. Only toward the end of the twentieth century, did they begin to resemble what one descendant called a “rainbow coalition.”

George (Jack) Pettiford’s moment of truth came when he was inducted into the Navy in World War II. When an official tried to put him in a white unit, he insisted that he serve with other blacks. As his widow, Jacqueline Pettiford, remembered, he kept being pushed toward the white side and had to keep going back to the black side, saying, ‘This is my line. I want to be what I am.’

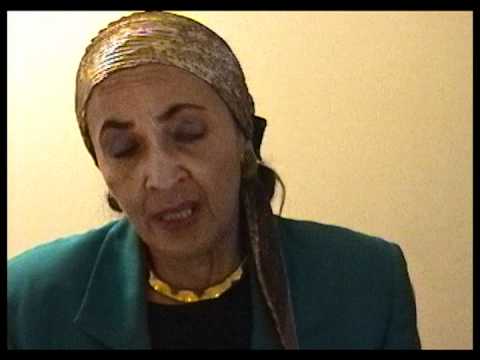

Madison Hemings’s great-granddaughter Patricia Roberts was often questioned about her ethnicity and some people suggested, “You don’t have to be black, you could be whatever you want.” Under no circumstance did she ever consider passing for white, she said. “That was the way we were brought up, to take pride in who we were.” Almost without exception, Hemings descendants interviewed for the Getting Word project—whatever they looked like—were proud to say, “I am black.”