The Infamous Craven Peyton Letter of 1803

While reading just about anything these days, it is not unusual to come across a Thomas Jefferson quote – sometimes real, sometimes not – but how often do you get what appears to be a complete Jefferson letter in the mail?

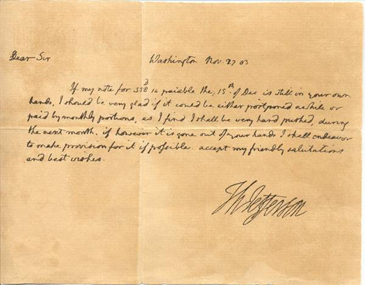

While serving as president, in November 1803, Jefferson wrote from Washington to ask Craven Peyton if a $558.14 note coming due in December could be put off or broken into smaller payments until the entirety was paid. If you have only ever heard a little about Jefferson’s income, debts, and spending habits you would probably not find the content of this letter very surprising.

But, in the midst of the Great Depression in 1936, Gary M. Underhill of the Morris Plan Bank of Richmond, Virginia, saw this letter as the perfect advertising gimmick. The bank directed the Richmond printing firm of Whittet & Shepperson to create 30,000 facsimiles on specially aged paper to use as part of a mass mailing promoting the Bank’s loan services.

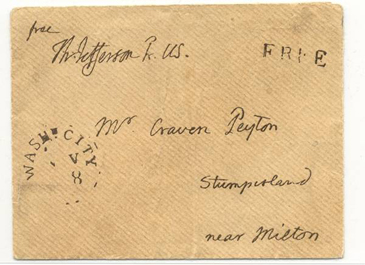

The facsimile letter, a modern-type envelope on the front of which was a facsimile of Jefferson’s address cover,

and an accompanying letter from the Morris Plan Bank, identifying the letter as a “reproduction,” were all mailed out together. But it seems that hundreds of the recipients discarded the advertising letters and kept the cool facsimiles, putting them away in trunks, cupboards, and file cabinets where they were discovered years later by unknowing family members.

The occasional discovery of these facsimiles began within just a few years of the original mailing in 1936 and they have continued ever since, generating a great deal of excitement for the discoverer and sometimes garnering the attention of local and national newspapers and magazines.

At least once every year I have the unpleasant task of having to tell someone that what they have got is not an original Jefferson document, but one of these facsimile letters.

Understandably, everyone is disappointed. Some get angry – but whether it is with me or with their family member (“why on earth did he keep this silly thing then?”), I cannot always tell. My favorite response though was from a gentleman who told me that he and his wife found the Morris Plan Bank story interesting, had a good laugh about it all, and have retained the facsimile as a conversation piece.

If you are interested, the original documents – both Craven Peyton’s received copy and Jefferson’s retained file copy – are in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

I have often been amused at the “modern” use of the Founders, their likenesses, and their words for the promotion of a wide variety of products. So, for me, the Craven Peyton letter facsimiles, together with their history as recorded in a variety of newspaper stories over the last several decades or so, provide an intriguing glimpse into the Depression Era and one bank’s creative attempt to attract business.