Welcome to Monticello and thank you for opening our mobile tour! Look for QR codes or click on each stop from our Navigation Page to learn more about Thomas Jefferson, the Monticello house, the Monticello plantation and to explore the lives of the people, enslaved and free, who called Monticello home.

If you have purchased a Self-Guided Tour of the house, you can access individual stops inside via QR codes as you travel through the first floor along the designated route. Explore outdoor stops in any order.

Audio Overview

Listen as Stephen Light, Director of Education and Visitor Programs, provides an introduction to Thomas Jefferson's life and the story of Monticello.

- Monticello was the plantation and home of Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United States and principal author of the American Declaration of Independence.

- Monticello is the only Presidential home in the United States designated as a World Heritage Site by the United Nations. Jefferson designed the house, calling it his “essay in architecture.”

- As a plantation, the vast majority of people who lived and labored here were enslaved people of African descent.

KEEP SCROLLING FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THESE TOPICS

Start Inside: Self-Guided House Tour Ticket Holders

Get ready to enter the house at the time on your Self-Guided House Tour ticket. Staff will gather groups five minutes before entry. Tour begins with the first room of the main house. Continue with outdoor self-guided stops after your tour.

First Indoor Stop »

Start Outside: All Ticket Holders

Explore the Monticello mountaintop at your own pace.

Outdoor Stops Map »

Highlights Tour or Behind the Scenes Tour Ticket Holders

Get ready to enter the house at the time on your ticket. Staff will gather groups five minutes before entry near where you got off the shuttle. Continue with outdoor self-guided stops after your tour.

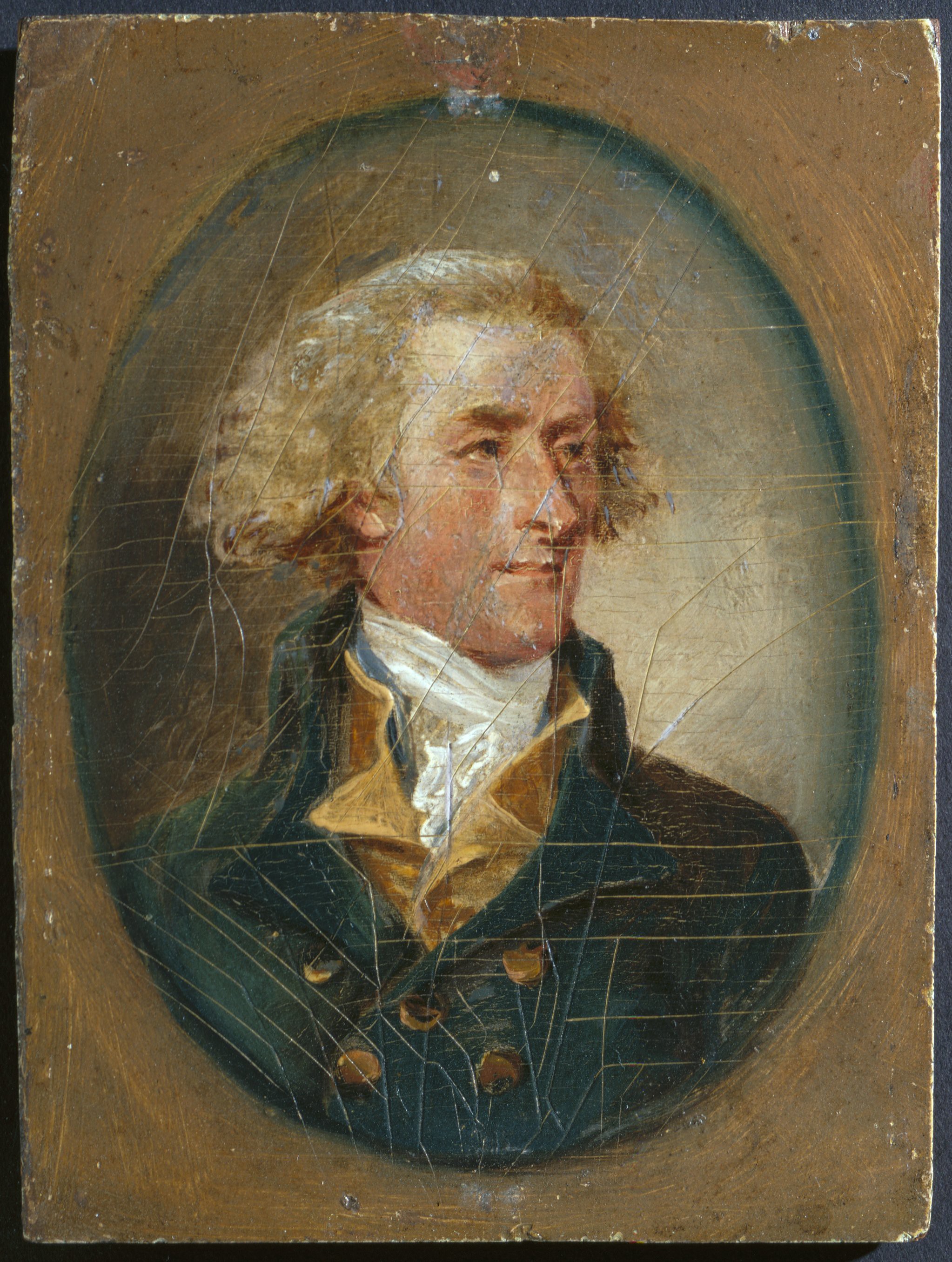

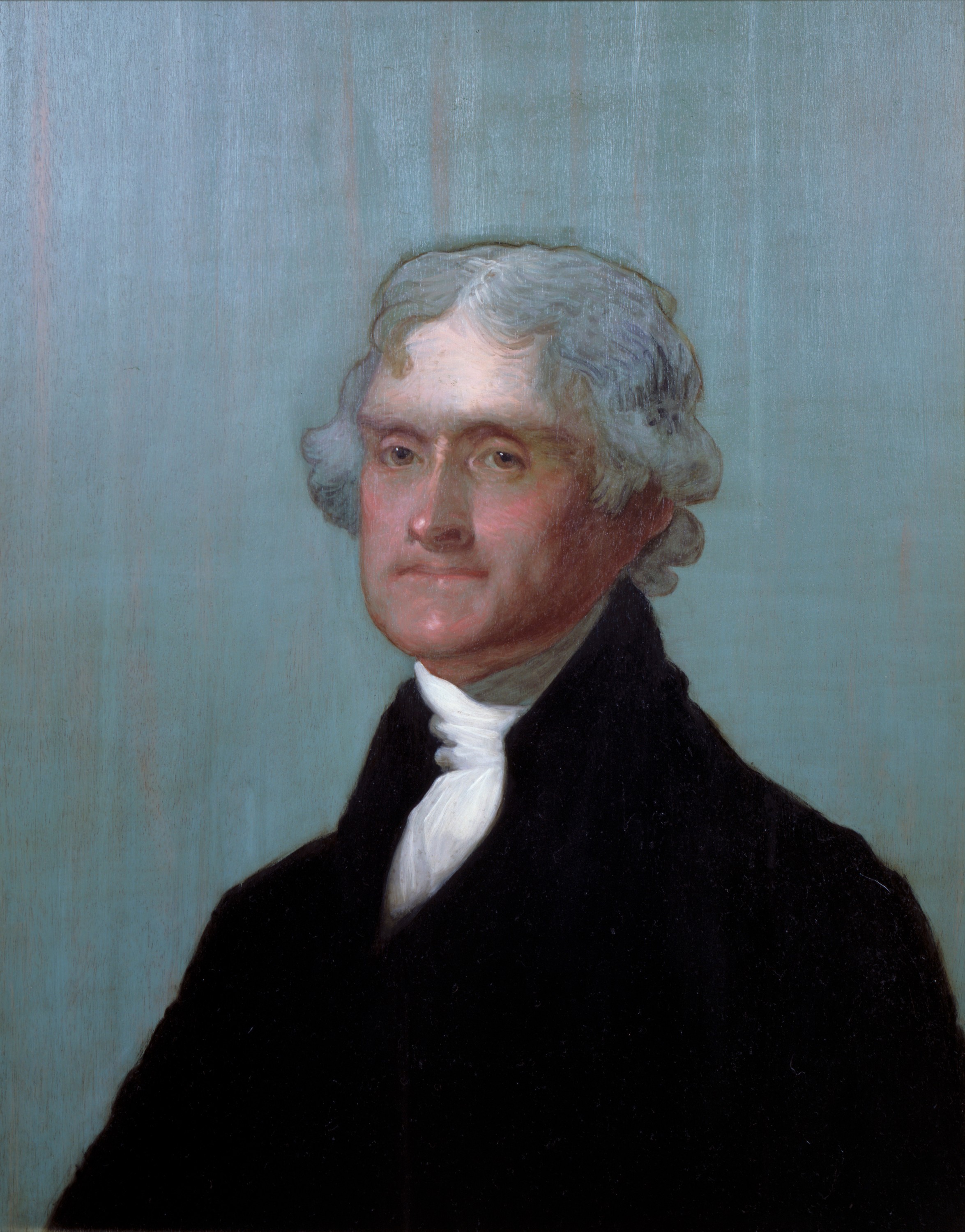

Thomas Jefferson: A Brief Biography

Thomas Jefferson was born at Shadwell, about two miles east of here, when this part of Virginia was the frontier of English colonization. Indigenous peoples lived in this area for millennia, and Jefferson documented the presence of the Monacan Nation who remain in Virginia today.

Jefferson was fourteen when his father died and he inherited land and human beings; Jefferson enslaved over six hundred people throughout the course of his life. Many of them lived at Monticello.

Jefferson attended the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, became a lawyer, and served in the House of Burgesses in Colonial Virginia by the age of 25. He joined those in opposition to tyrannical British rule and represented Virginia in the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where he wrote the Declaration of Independence at age 33.

Jefferson’s words justifying independence from Great Britain contain a powerful and universal message for self-governance, equality, and human rights that continues to inspire people in America and around the globe to make his words a reality for all mankind.

Throughout his life, Jefferson wrote about the problem of slavery. He consistently denounced the institution, but his personal wealth and comfort came from enslaving people, and like many wealthy white planters, he believed in a racial hierarchy and argued that lighter skinned people are superior to darker skinned people. The legacies of this erroneous belief remain with us today.

In 1772 Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton and in ten years of marriage they had six children; only two survived to adulthood. Jefferson was devastated by Martha's death in 1782, following the birth of their last child.

Jefferson served briefly in the Confederation Congress before moving to Paris, where he served as U.S. Minister to France from 1784 to 1789. During these years, Jefferson brought four people from Monticello to Paris: his daughters, Martha and Maria, and, as his cook and his daughters' ladies maid, the enslaved siblings James and Sally Hemings. When they all returned to the United States, Sally Hemings was pregnant with the first of her children, all of whom were fathered by Thomas Jefferson. Their surviving children were allowed to escape or were provided legal manumission as adults.

Back in the United States, Jefferson served as Secretary of State (1790 - 1793), Vice President (1797 - 1801), and for two terms as the third President (1801 - 1809). After creating the idea of America in writing the Declaration of Independence and serving the new nation for almost forty years, Jefferson returned to Monticello in 1809, and never left Virginia again.

His daughter, Martha, who married Thomas Mann Randolph Jr., and her family joined Jefferson at Monticello, where he was surrounded by their eleven children. During his retirement here, Jefferson devoted his time to a project he called “the hobby of my old age,” founding and designing the University of Virginia, partially fulfilling his life-long vision to create a system of public education.

Here at Monticello, on July 4th, 1826, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson died, the same day as his old friend John Adams.

Jefferson left behind specific instructions for his tombstone and wrote his own epitaph. He wanted only three of his achievements listed. He was the author of the Declaration of Independence, Author of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and Father of the University of Virginia. Jefferson wanted future generations to remember that he dedicated his entire life to that constant fight for the freedom of government, the freedom of religion, and what he so eloquently called “the illimitable freedom of the human mind.”