Jefferson Began Building Monticello 250 Years Ago

On February 5, 1769, Thomas Jefferson replied to his cousin’s request that his son study law under him. Writing from Shadwell, his boyhood home, Jefferson said he must decline: "I do not expect to be here more than two months in the whole between this and November next, at which time I propose to remove to another habitation which I am about to erect." That new house, he wrote, would be not large enough to accommodate his son. This is the first reference in any Jefferson letter that he was building a new house.

The 1770 “outchamber” was the first Jefferson-designed building ever built and the first brick building constructed on the Mountaintop. Digital renderings by RenderSphere, LLC. Click image to enlarge.

Panoramic image of Monticello and Mulberry circa 1784 (Phase I). Digital rendering by RenderSphere, LLC. View the full screen pano »

Jefferson, then 25 years old, was characteristically optimistic—not until November 1770 would he occupy the structure today known as the South Pavilion or "Honeymoon Cottage." But construction began in 1769, and this year marks the 250th anniversary of the start of the home Jefferson would call Monticello, or "little mountain" in old Italian.

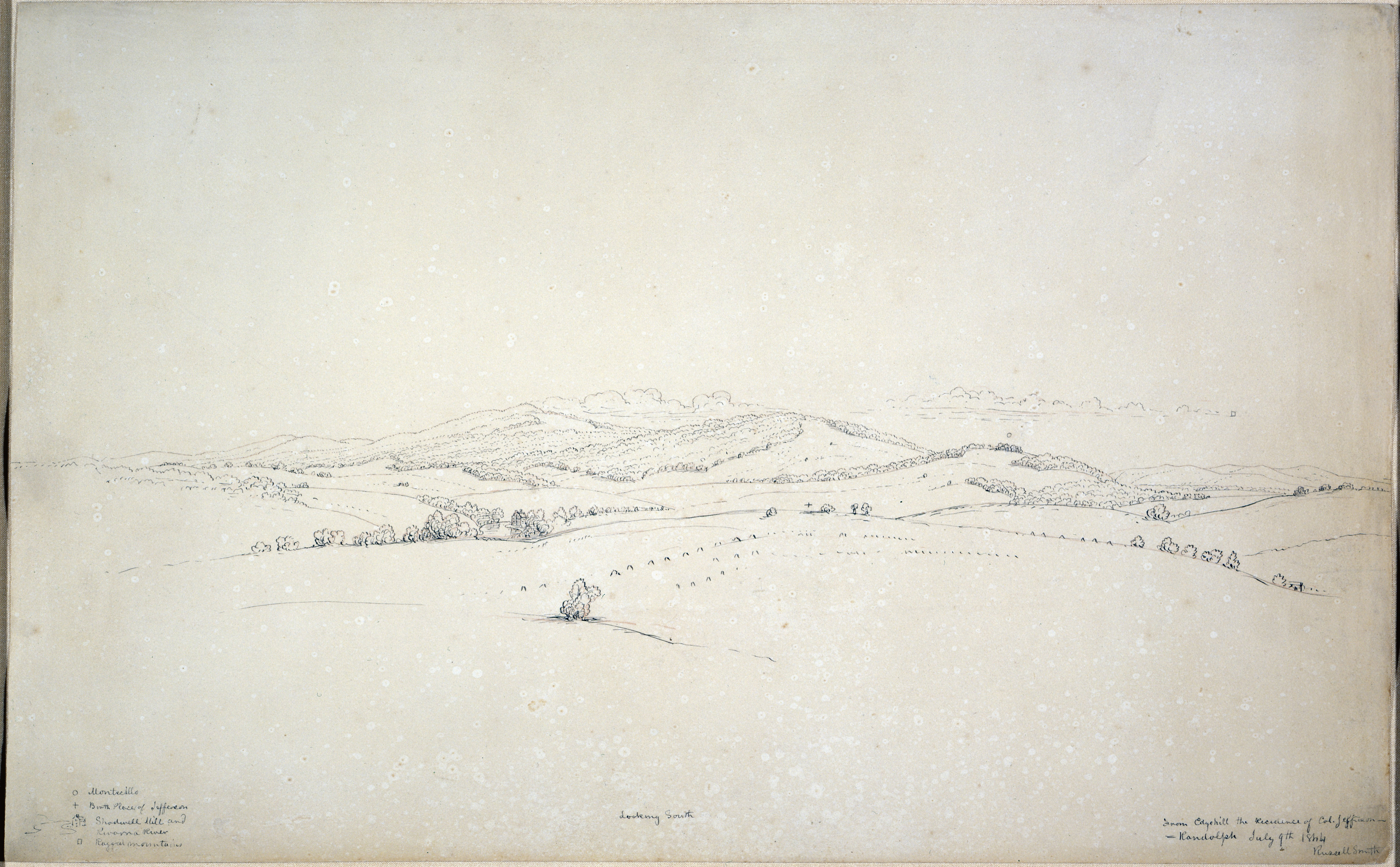

View of Montalto and Monticello mountains from Edgehill by Russell Smith (1844). Click image to enlarge.

View of Montalto and Monticello mountains from Edgehill by Russell Smith (1844). Click image to enlarge.

Monticello began with a boy’s vision. To stand today on Shadwell’s grassy fields is to imagine a young Jefferson gazing at the little mountain and wondering why he lived on the plain and not on the heights. Jefferson’s daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, recalled her father explaining “that when quite a boy the top of this mountain was his favorite retreat . . . and that the indescribable delight he here enjoyed so attached him to this spot that he determined when arrived at manhood he would here build his family mansion.”

The view of Monticello, or “little mountain,” that Jefferson first saw as a boy. Monticello is the right-hand lower hill while to the left is Montalto. Click image to enlarge.

The view of Monticello, or “little mountain,” that Jefferson first saw as a boy. Monticello is the right-hand lower hill while to the left is Montalto. Click image to enlarge.

Jefferson was already a busy man when construction started. He was about to take his seat in the House of Burgesses and was two years into his law practice, traveling the circuit making modest sums. Though Jefferson had inherited that part of his father’s estate which included the little mountain and about 20 slaves, he was far from a wealthy man and he surely knew how expensive and difficult building a mountaintop home would be. Most problematic was water—it was impossible then to dig a well deep enough on a mountaintop to obtain reliable water, and among the projects undertaken in 1769 was digging a well near the South Pavilion. Jefferson observed that three enslaved workers digging his well removed about 40 cubic yards in a day. He also noted that the soil was rocky, with several stones removed that were “as large as a man’s head.” But despite reaching a depth of 66 feet, the well proved unreliable; Jefferson’s records show several instances of it failing to provide any water for months at a time. Another problem was the expense of transporting supplies up what one visitor described as a “steep, savage hill . . . as pensive and slow as Satan’s ascent to Paradise.” Jefferson addressed this by designing several miles of winding roads to ease that climb, roads built and maintained by slaves.

Most of the construction efforts in 1769 centered on accumulating building materials. George Dudley and a crew of brickmakers arrived in July to produce some 45,000 bricks. In September Jefferson contracted with George Sorrel to fabricate 8,000 chestnut boards and stipulated that they were “not to be counted until they were put up.” By October Jefferson was ordering items for “the house,” including door hardware and “cord etc. for Venetian blinds.”

Jefferson's freehand elevation of Monticello I, ca. 1777. Click image to enlarge.

Jefferson's freehand elevation of Monticello I, ca. 1777. Click image to enlarge.

Jefferson could not have foreseen that the house begun 250 years ago would one day become a national treasure and a World Heritage Site. Given the difficulties, what he called “his essay in architecture” might have ended in failure. That Jefferson began such a project, and brought it to fruition, remains an enduring testament to his vision, ambition, and determination.