Jefferson’s Competition in the Nail Selling Business

As the nineteenth century begins, down inside the “Dungeons” of the brand new Virginia State Penitentiary, a prisoner uses machine shears to cut nails from nail rod. In a Richmond newspaper, Kate McCall advertises for “Two or three Apprentice boys” who could join her enslaved workers at McCall’s nail manufactory, located less than a mile from the Penitentiary. Seventy-three miles away, enslaved boy Jamey Hubbard hammers at nail rod furiously so that he may win meat rations from Thomas Jefferson at the Monticello plantation.[1] What connects these three historical snapshots? Each depicts powerful Virginians forcing others to make nails for sale in the robust Richmond market. More importantly, they illustrate three surprising competitors in this race to sell nails: the well-known Thomas Jefferson, an unmarried white woman, and “the state”—made up of taxpayers, penitentiary staff, and politicians.

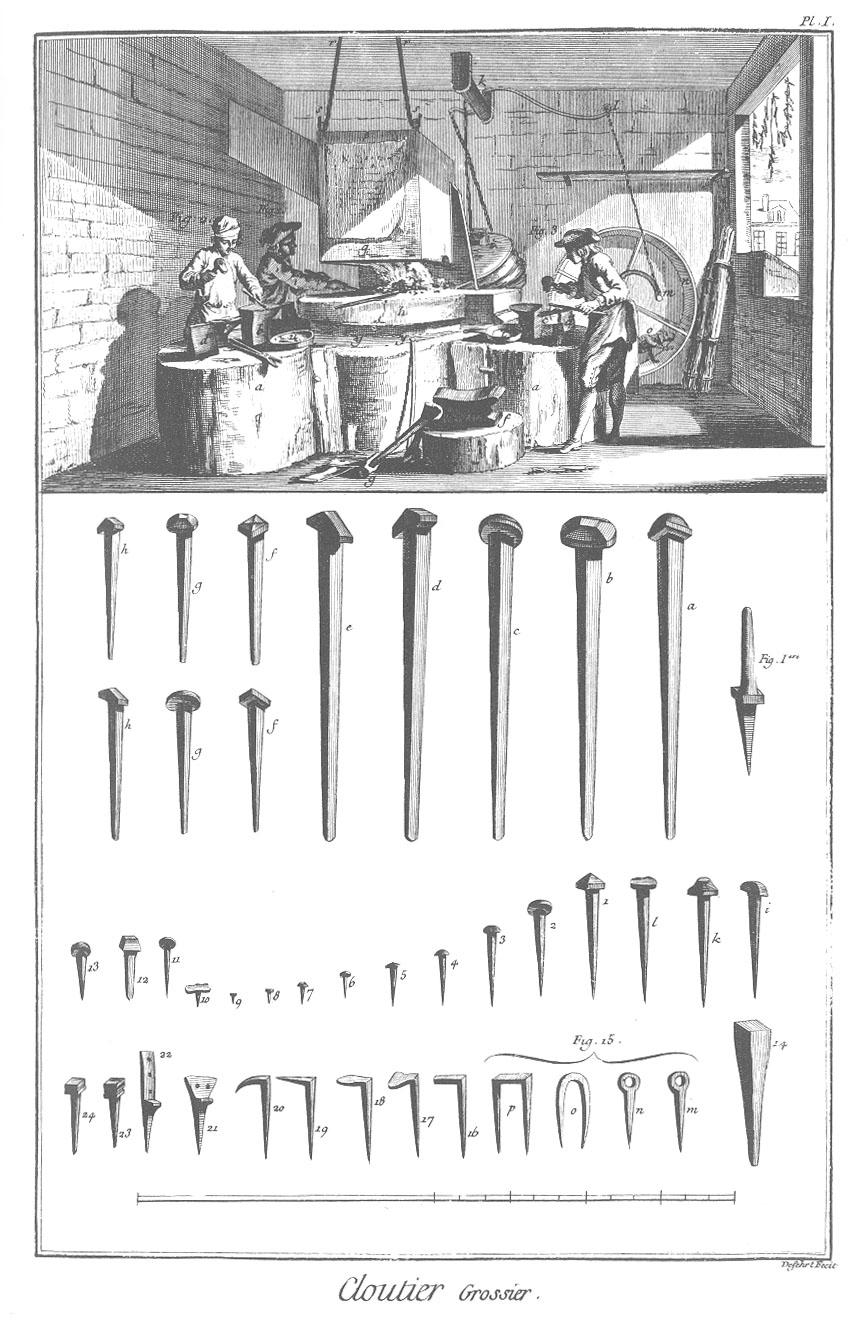

Workshops located on Jefferson’s Mulberry Row included a nailery, which became operational in 1794. Jefferson hoped the nailery would become a source of cash income where “a parcel of boys who would otherwise be idle”[2] could turn “tons of nail rod into thousands of nails” (as historian Cinder Stanton put it). A dozen or so of Jefferson’s enslaved teenagers (such as Hubbard and Isaac Granger) worked ten- to fourteen-hour days repetitively making nails in the hot and smoky shop.

The demand for the product was high, since nails were necessary to construct the wooden buildings rapidly emerging in Virginia’s urban centers. Virginia proved a state fertile for the growth of iron industries, given its large forests, plentiful ore deposits, and enslaved labor system. And because the James River powered mills and ironworks and provided transportation for goods, Richmond developed as a center of southern industry in the early nineteenth century. Jefferson’s nailery operated until 1823, and its profits peaked in 1795 when his enslaved boys produced 8,000 to 10,000 nails a day and provided “completely for the maintenance of [Jefferson’s] family.”[3]

Nailery and Blacksmith’s Shop on Mulberry Row, Monticello. 3D model by RenderSphere, LLC. (https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/nailery)

Like Jefferson, other capitalists sought to profit from making and selling nails in Richmond. One is the subject of my research: Catharine “Kate” Flood McCall, a never-married slave owner who founded “McCall’s Basin on the Edge of the Canal” with her father in 1805. McCall hired free and enslaved workers to man her enterprise, and frequently advertised the wares she sold: wrought nails, cut nails and brads, bar iron, nail rod, and “All kinds of Blacksmith’s work.”[4] While a woman owning enslaved people proved far from rare in nineteenth century Virginia, a single woman who ran her own industrial enterprise certainly was. McCall eschewed suitors all her life, and invested in enslaved people, land, and her nail-making enterprise. Virginia’s laws at the time considered McCall a feme sole (“single woman”). This meant that while she couldn't vote or serve on a jury, she could legally act like a man: she could control her property and earnings, sign contracts, and sue (and be sued). Married women (feme coverts) could do none of these in their own name. Seeking her own profit, McCall, like Jefferson, chose low-skilled nail making to pursue that end.

Kate McCall was one of President Jefferson’s many contenders in the race to sell nails in Virginia’s growing cities. But Jefferson knew of the McCall family before Kate became his competitor. In 1802, Archibald McCall (Kate’s father) wrote to ask Jefferson if he would pay for “the Loss my Daughter sustained” because of the mismanagement of the estate of Kate’s maternal grandfather, Dr. Nicholas Flood (Jefferson’s father-in-law John Wayles had owed money to Dr. Flood).[5] In an 1803 letter to Archibald McCall, Jefferson refers to other legal and financial issues that connected the McCall, Jefferson, Skelton, and Peachey families.[6] Could Jefferson have predicted that the daughter of a man he once quibbled with about inheritances would soon turn into his competitor for nails?

Jefferson and McCall both competed with another seller of nails in Richmond: the Virginia State Penitentiary (built in 1800). Revolutionary ideals and labor concerns encouraged reform-minded lawmakers (including Jefferson himself) to construct state penitentiaries across the new nation. The Virginia State Penitentiary embodied reformers’ views that labor produced morality, which produced economy. The Penitentiary would turn hard criminals into reformed citizens of the new republic by making them manufacture goods for sale, which would benefit taxpayers. Since the very first enterprise the Penitentiary set up was a nail-making room, the low-skilled nature of nail making also incentivized the Penitentiary to invest in this industry. The Penitentiary became profitable by 1807 by selling prisoner-made nails and other goods to Richmond locals.

Ironically, the Virginia State Penitentiary's entrance into the Richmond nail market in the early 1800s undercut the capital city's "free" labor market for this good. So successful was the Penitentiary that it undersold many privately owned nail firms in Richmond, including “McCall’s Basin on the Edge of the Canal” by 1815. The timing of when McCall and Jefferson began to lose profits, and then finally closed their nail shops—as the Virginia State Penitentiary reached its zenith in profits—is certainly not a coincidence.

The state, Kate McCall, and Thomas Jefferson all profited from the labor of unfree people who hammered away to make nails for sale in Virginia. President Jefferson’s administration promised citizens like McCall individual freedom to conduct business with limited government intervention. But the entrance of the Virginia State Penitentiary into Richmond’s nail market demonstrates that, ironically, Jefferson perhaps undercut his own vision as some citizens called into question the ability of private enterprise to flourish in the new republic. Today, private prisons profit from the low-paid or unpaid work that prisoners perform, having dispensed with the explicit defense of “enlightenment.”

Alexi Garrett received her Ph.D. from the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia. She is the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies and University of Virginia Press Post-Doctoral Fellow at Iona College (2020-2022). She was a fellow at the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies in 2019.