Evolution of the Project

by Christine Andreae, May 2009

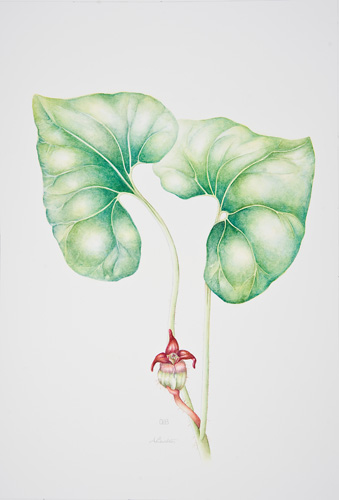

The Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks project evolved from a 2006 exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. It was called “Botanical Treasures of Lewis and Clark” and it featured portraits of plants collected by Meriwether Lewis during the Lewis and Clark Expedition. One of my pieces in the show was a collaborative work with seven contributing artists: a small, accordion album titled “Rations and Remedies.” When it was unfolded, it displayed graphite drawings of edible and medicinal plants that Lewis had written about in his journals. While researching “Rations and Remedies,” I learned that Lewis didn’t actually “discover” many of the plants; rather, hospitable native peoples introduced them to him. Indian breadroot (Pediomelum esculentum) and bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva), for example, were offered to him as food. I also learned that Lewis’ mother Lucy was a noted healer in Albemarle County, Virginia, and that as a boy he had learned the uses of healing herbs and simples from her. On his Voyage of Discovery, he used counterparts of eastern plants like chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) and wild ginger (Asarum caudatum) to treat himself and his men. Indirectly, Lucy had a vital hand in the success of her famous son’s great adventure. But who was Lucy? A pioneer woman in a dirty apron? A landed aristocrat waited on by slaves?

This was the germ of the Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks project: to discover who she was, which plants she would have used as a “doctoress,” and to celebrate her herbs in botanical portraits. My friend Patricia Zontine agreed to help me research. Nine botanical artists joined us and we organized two workshops, the first to introduce them to Lucy and healing herbs, the second to critique works in progress. We were unprepared, and happily surprised, to find that our project had a life of its own. It quickly mushroomed from an art show of healing plants into a multi-dimensional exploration of 18th-century medicine, Lucy’s extensive family clan, and her role as female planter and slave-owner. Historians and genealogists joined us. Botanists, an herbalist, a doctor of pharmacology, a medical historian advised us. Lucy’s descendants provided documents and artifacts. Jack Robertson, Librarian of the Jefferson Library, gave our paintings an elegant physical venue and provided this virtual home for our research.

At the outset, we hoped to find some of Lucy’s papers – a garden book, perhaps, like the one her neighbor Thomas Jefferson kept. A ledger of medicinal recipes. A slave book recording births and deaths. But as close as we came to her own hand was her signature on a power of attorney in the Special Collections at the University of Virginia. We know from her will that she owned a small library – unusual for a woman in those days. But we could find no record of the titles of her books. Surely she owned herbals. But which ones? Rather late in the game, we learned that there was a fire at her home at Locust Hill not long after her death, so perhaps her books and papers were destroyed in the fire.

Still, it is surprising how much information about her we were able to piece together from scraps: a letter from a slave, a receipt for lumber, mention of a crop, a family story about how she disciplined her children. Like a quilt from Lucy’s day, this website, with its “piecework” and its layers, was created by a community of hands. Unlike an old quilt, however, it is not finished with a border. We hope that new documents will surface and that we will be able expand and enrich this site as a permanent resource of the Jefferson Library.

We are deeply grateful to the Jefferson Library and to Librarian Jack Robertson for his creative support and advice. Special thanks to the unflappable and cheerful Eric Johnson, the designer of this site and to our many consultants: Leslie Exton, Guy Meriwether Benson, Dr. Wendell Combest, Peggy Cornett, Jane Henley, Kathleen Maier, and Dr. Todd L. Savitt. Their expertise in so many different disciplines has helped keep us on track. We are indebted to the Home Chapter of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation and Doug Valentine for their help and support. We are also indebted to the generosity of our family members and friends who became sponsors and helped make our project happen: Carol Andreae & Jim Garland, Sue & Hewett Brown, Anna Collins & Sue Morrison, William G. Dakin, Vicki & Pat Malone, Dahne & Chip Morgan, Kay & Bill Schrenk, Phyllis M. Wyeth, and The International Academy for Preventive Medicine. A heartfelt thanks to our anonymous donor whose early and major gift to the project was a wonderful impetus and vote of confidence.

And last, but not least, a special thanks to our spouses who, during the two rather obsessive years of this project, cheerfully became “Lucy widowers”.