The Business of Slavery at Monticello

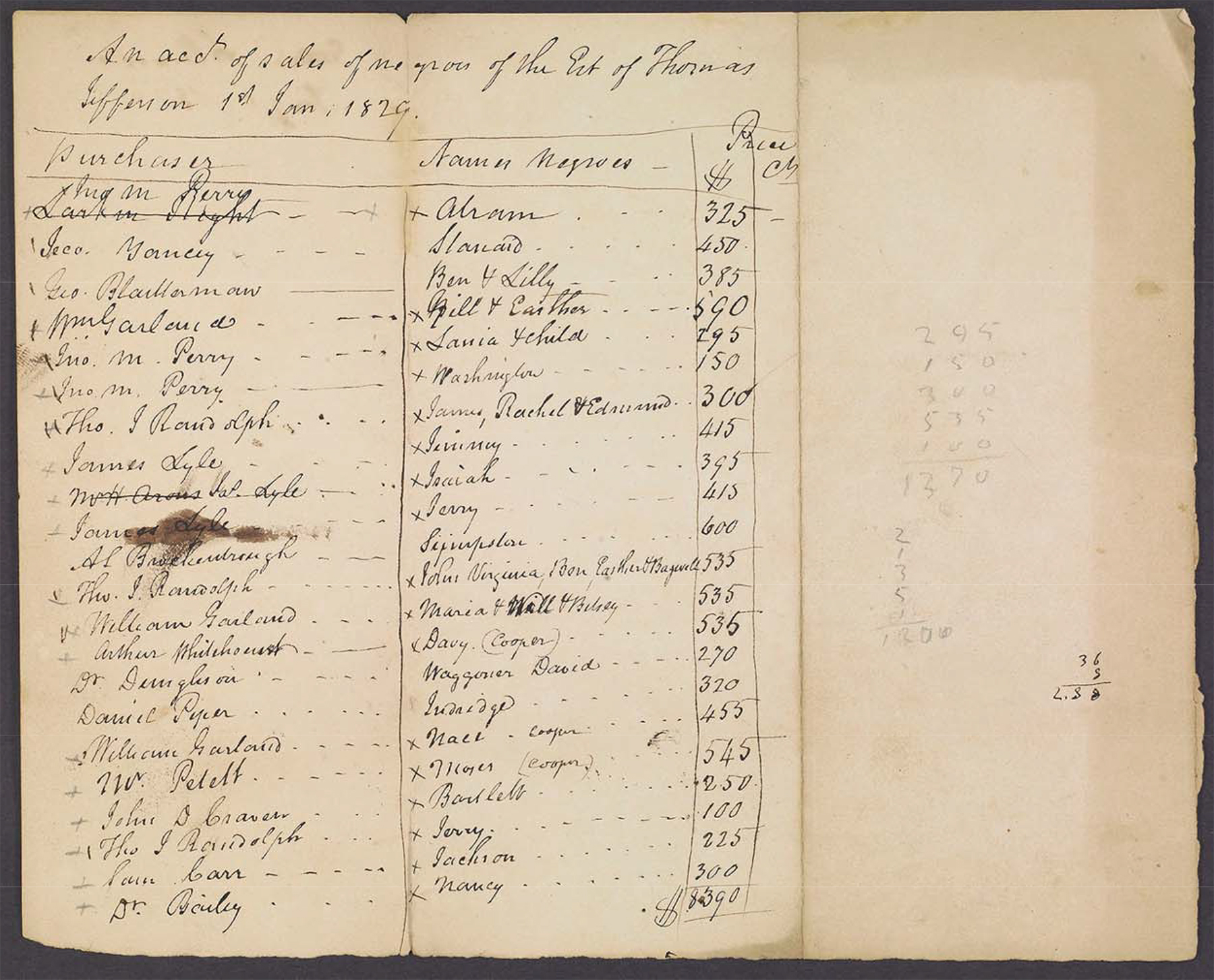

Bill of sale from 1829 Slave Auction in Charlottesville showing Mr. Garland purchasing "Gill & Esther" for $590.

In 1820, Gill Gillette embarked on a long journey at Thomas Jefferson’s behest. Traveling from Buckingham County to Richmond, the enslaved man carried a “paper of great consequence” that was sewn inside his waistcoat. The “paper” Gillette transported with “special care” was actually a check drawn on the Bank of Virginia for $3,500. What Gillette could not have known was that the check he carried was payment for the sale of men, women, and children at Jefferson’s Poplar Forest plantation to his son-in-law, John Wayles Eppes. Gillette may not have been included in this particular slave sale, but nine years later, he and his wife Esther would be sold on the auction block at Monticello to William Garland for $590. Prior to that, Gillette’s status as human property had allowed Jefferson to both mortgage him and lease him out to a tenant farmer.[1]

Jefferson—and his world—was defined by the institution of slavery. Although he declared in 1788 that “nobody wishes more ardently to see an abolition not only of the trade but of the condition of slavery,” Jefferson owned 607 people in his lifetime, having inherited 52 slaves from his father’s estate and an additional 135 individuals from his father-in-law, the slave trader John Wayles.[2] The remaining slaves were born into captivity or, as was the case for about 20 enslaved people, purchased outright. Between 1776 and 1826, Jefferson kept between 165 and 225 slaves on his Virginia plantations, with about three-fifths of his human property at Monticello and two-fifths at Poplar Forest, his estate in Bedford.[3] Although Jefferson imagined himself to be a benevolent slaveholder who would “watch for the happiness of those who labor for mine,” he still thought of enslaved people as his chattel.[4] Jefferson profited not just from the tobacco, corn, and wheat that his slaves grew in the crop fields, but also from the value of their bodies and, particularly, their natural increase. As property, the enslaved men, women, and children who belonged to Jefferson could be leased, mortgaged, bought, sold, willed and given away. As the case of Gill Gillette makes clear, every slave that Jefferson owned was subjected to at least one of these features of the American slave market.

Jefferson’s Virginia plantations were part of an expanding—and increasingly commercial—American slave system in the post-revolutionary era. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, new “free land” that became available in the southwest after U.S. federal troops “removed” native tribes opened the door to cotton cultivation. This land was cleared and drained in anticipation of what would later become the “cotton belt,” a vast swath of country that began in the upcountry of the Carolinas and extended westward through Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and later Texas. The millions of “hands” needed to build this new cotton empire helped initiate a robust and tragic innovation of the antebellum era: the increased value and commoditization of slave bodies. As a result, in the nineteenth century, the commercialization of the American slave empire—leasing, mortgaging, insuring, and buying and selling human chattel—indicated not simply the survival of slavery, but also the speed and scale of its expansion.[5] And Virginia played a crucial role. With the self-reproduction of its slave population, which increased from 287,959 in 1790 to 453,698 in 1830, Virginia became, as the former slave Louis Hughes recalled, the “mother of slavery.” Not only did Virginia claim the largest slave population in the federal union, but it also served as the primary supplier of enslaved laborers to other states through the domestic slave trade, which transported nearly one million enslaved men, women, and children to the Deep South between 1820 and 1860.[6] Like many other Virginia planters, Jefferson engaged in the business of slavery: he bought, sold, mortgaged, and leased enslaved people in order to accrue wealth and maintain his elite status. But unlike many planters, Jefferson often engaged in these markets not just for material gain, but also—somewhat paradoxically—for what he saw as humanitarian reasons. Reasoning that “our interests soundly calculated will ever be found inseparable from our moral duties,” Jefferson subjected his human property to the hiring and mortgaging markets in an effort to shield them from what he considered the most “evil” market of all: the slave trade.[7] But Jefferson often failed in this endeavor, primarily because he found himself unable to manage the massive debts incurred by himself, his parents, and his father-in-law. As even Isaac Granger Jefferson, once enslaved at Monticello, knew, the “portion” of property that Jefferson “acquired by marriage was encumbered with a (British) debt & resulted in a heavy loss.” In an effort to satisfy these debts, which mushroomed to over $107,000 by the time of his death in 1826, enslaved people, as Jefferson’s most valuable property, were often sold on the auction block.[8]

Viewing selling as a last resort, Jefferson turned to leasing and mortgaging those he enslaved for income. Jefferson’s ability to hire the enslaved out and use them as collateral to secure loans was based on the increased value of slave bodies and the “natural increase” of the population held in bondage. Unlike in the Caribbean, this increase allowed Virginia planters to satisfy the demand for slave labor without having to import slaves from Africa. Jefferson himself encouraged the reproduction of those he enslaved. In particular, Jefferson understood that the women he enslaved—and their future children—represented the best way to increase the value of his holdings, what he called “capital.” “I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm,” Jefferson wrote in 1820. “What she produces is an addition to the capital,” while a male slave’s “labors disappear in mere consumption.”[9] In 1819, worried by a spike in infant mortality at Poplar Forest, Jefferson believed that it was for “moral as well as interested considerations” that overseers should preserve slaves’ lives, not for “their labor, but their increase.”[10] As Jefferson’s friend and neighbor John Hartwell Cocke observed, Virginia slaveowners increasing believed that their “profits consists in the increased number & value of their slaves,” rather than in the crops that their bondspeople produced.[11]

Jefferson argued that renting out those he enslaved could generate a profit without having to sell them. “Hiring presents a hopeful prospect,” Jefferson declared, as it would allow him to retain ownership of enslaved people and possibly free them in future time. Buckling under the weight of his crushing debts, Jefferson thought he had only two options. “In a question between hiring and selling them[slaves] (one of which is necessary),” he wrote, the “hiring will be temporary only, and will end in their happiness,” which Jefferson defined as improved material conditions and the ability to remain with their families. On the other hand, he wrote, “if we sell them, they will be subject to ill usage without a prospect of change” and likely be sold southward. Jefferson felt the “weight of the objection” for either option, since “we cannot guard the negroes perfectly against ill usage.”[12]

As a result, Jefferson embraced the market in rented slaves, hiring out over 100 of those he held in bondage to local artisans and tenant farmers who leased portions of his 5,000-acre plantation, which was comprised of the Shadwell, Monticello, Lego, and Tufton quarter farms.

In the 1790s, Jefferson capitalized on the increasing number and value of his slaves to do two things—increase his access to capital and shield his enslaved property from foreclosure. In 1796, Jefferson feared legal action from claims brought against the estate of his father-in-law. Under Virginia law, creditors could seize human property to satisfy debts. To prevent his bondspeople from being sold to absolve the Wayles debt, Jefferson sought an alternative approach. He first mortgaged 52 slaves to Henderson, McCaul & Company, and then gave as collateral 98 other slaves to several friends and the Dutch firm of Van Staphorst & Hubbard. Jefferson received a nominal loan of $2,000 from Van Staphorst & Hubbard, which was never paid off entirely. The enslaved mortgaged to Jefferson’s Dutch bankers included the families of Ned and Fanny Gillette and Bagwell and Minerva Granger, among several others. These mortgages demonstrated that an indebted Jefferson was trying to circumvent a legal obstacle—slaveholders could not use verbal conveyances, or emancipation, to prevent slaves from being seized by creditors. His solution was to give mortgages to friendly creditors who were unlikely to take his slaves. It also enabled him access to credit that he sorely needed.[13]

Following the American Revolution, mounting financial pressure meant that Jefferson did often turn to the sale of both land and those he enslaved. Between 1784 and 1794, Jefferson sold 84 slaves. At his Elkhill plantation, in Goochland County, Jefferson directed that 31 slaves be sold in 1785. About seven years later, he sold three more groups of slaves from his Albemarle and Bedford estates. In December of 1791, 29 enslaved people yielded over $4000 on the auction block; another sale a year later in Bedford County brought nearly $2000 for 11 people. And, in January of 1792, 13 slaves were sold away from Monticello. Together, these sales netted Jefferson over $15,000. Jefferson sold more slaves in this ten year period than at any other time prior to his death. But ultimately, even the sale of dozens of people and several plantations was not enough to satisfy Jefferson’s debts.[14]

Jefferson also engaged in the slave trade for reasons other profit. He well understood the horror that sale and separation meant for enslaved people—and he sometimes employed it as the ultimate punishment for chronic runaways and slaves who committed violent acts. Although Jefferson maintained that he had “scruples against selling negroes,” he sold them willingly for such “delinquency.”[9] In 1822, when three Poplar Forest slaves—Hercules, Gawen, and Billy—were charged with stabbing an overseer and “wickedly and feloniously having consulted upon the subject of rebelling and making insurrection,” Jefferson directed that they be transported South “as an example to N. Orleans to be sold.”[16] When the chronic runaway, Jame Hubbard, was forcibly recovered from his second quest for freedom, Jefferson advised that he be sold “out of the state” since “he will never again serve any man as a slave.”[17] When the enslaved nailmaker Cary nearly killed fellow enslaved nailer Brown Colbert with a hammer, Jefferson wanted to “make an example to him in terrorem to others.” Cary was to be sold to “negro purchasers” to a “quarter so distant as never more to be heard of among us.” Jefferson inflicted the ultimate punishment of “exile” from home and family.[18]

But it was when the slave auction block finally came to Jefferson’s mountaintop after his death that it became clear just how deeply entangled Monticello was in the commercial world of American slavery. The constant threat of sale and separation was a cruel reminder to Monticello’s African American families of their legal status as property and of the horrors of a slave system that profited from their bodies and their labor. In an effort to satisfy some of the enormous debt that Jefferson left to his white heirs when he died in 1826, 126 men, women, and children were put on the auction block in 1827, and a further 30 people were sold in 1829. The buyers of these enslaved people, whose value constituted over 90 percent of the $31,400 appraised value of Jefferson’s estate, included University of Virginia professors, local merchants, former Monticello overseers and artisans, and Randolph family members. Awaiting an uncertain fate, examined and bid on by slave traders and white neighbors, many Herns, Hemingses, Grangers, Hubbards, and Gillettes saw their family members for the last time. While several enslaved people continued to live with their new owners in Albemarle County, many more were taken to cotton country, to places like Mississippi, Missouri, Arkansas, and Alabama.[19]

For the enslaved families of Monticello, Jefferson’s death was a tragic turning point in their lives that underscored their identities not as people, but as property. Israel Gillette Jefferson recalled that Jefferson’s passing was “an affair of great moment and uncertainty to us slaves.” And 11-year old Peter Fossett remembered that while he was “born and reared as free, not knowing that I was a slave” at Monticello, his owner’s death “suddenly” placed him “upon an auction block sold to strangers.” Fossett was one of many children to be separated from parents and siblings during the 1827 and 1829 sales. Though Fossett “resolved to get free, or die in the attempt,” it would take him another 23 years—and two failed runaway efforts—to finally find freedom and rejoin his family in Ohio. But many African American families from Monticello were never reunited and remained “scattered all over the country.” Years after the Monticello slave auctions, Israel Gillette Jefferson never heard from his four children—Banebo, Taliola, Susan, and John—again. “As they were born slaves, they took the usual course of most others in the same condition in life,” he wrote. “I do not know where they now are, if living; but the last I heard of them they were in Florida and Virginia.” The legacy of a slave system that defined African Americans as chattel, as well as the permanent separation of so many family members, left its tragic imprint on Monticello’s slave families for generations. As Hemings descendant Virginia Craft Rose recalled nearly 200 years after several of her ancestors were sold at auction at Monticello: “we couldn’t forget slavery, but we could overcome it.”[20]

Learn More: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery

Explore: Slavery at Monticello Mobile Guide

Explore: Slavery at Monticello Mobile Guide

Available in Our Online Shop: "Those Who Labor for My Happiness"

Available in Our Online Shop: The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family

References

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to John Wayles Eppes, 13 October 1820,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-1583; Account of the Sale of Slaves from Thomas Jefferson’s Estate (1829), http://tjrs.monticello.org/letter/2340.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to Brissot de Warville, 11 February 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-12-02-0612.

- ^ Lucia Stanton, ‘Those Who Labor for My Happiness’: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012), 106-7.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to Angelica Schuyler Church, 27 November 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-27-02-0416.

- ^ Peter S. Onuf, “The Empire of Liberty: Land of the Free and Home of the Slave,” in Andrew Shankman, ed., The World of the Revolutionary American Republic: Land, Labor and the Conflict for a Continent (New York: Routledge, 2014), chap. 9; Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Vintage Books, 2014); Joshua D. Rothman, Flush Times and Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012); Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery, Capitalism, and Imperialism in the Mississippi Valley’s Cotton Kingdom (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013); Calvin Schermerhorn, The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

- ^ U.S. Census, 1790, 1830; Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999); Louis Hughes, Thirty Years a Slave: From Bondage to Freedom (Milwaukee: South Side, 1897), 31.

- ^ Jefferson, Second Inaugural Address, 4 March 1805,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-1302.

- ^ Life of Isaac Granger Jefferson (1847), https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/_Life_of_Isaac_Jefferson_of_Petersburg_Virginia_Blacksmith_by_Isaac_Jefferson_1847.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to John Wayles Eppes, 30 June 1820,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-1352.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to Joel Yancey, 17 January 1819,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-0039.

- ^ John Hartwell Cocke to unknown, September 31, 1831, Cocke Family Papers, Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to Nicholas Lewis, 29 July 1787, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-11-02-0564.

- ^ Samuel Shepherd, ed., The Statutes at Large of Virginia, from October Session 1792, to December Session 1806 …, Richmond, 1835–36, 3 vols.description ends i, 128-9; Robert McColley, Slavery and Jeffersonian Virginia, Urbana, Ill., 1964 80–1; Dumas Malone, Jefferson and his Time, Boston, 1948–81, 6 vols., III, 179.

- ^ Betts, ed., Jefferson’s Farm Book, “Negroes Alienated from 1784 to 1794, inclusive,” 25.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to John Wayles Eppes, 30 June 1820,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-1352.

- ^ William Radford to Thomas Jefferson, 26 December 1822,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-3237; Bedford County Order Book, No. 18, pp. 318-19; Thomas Jefferson to Bernard Peyton, 5 January 1824,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-3963.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to Reuben Perry, 16 April 1812,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-04-02-0508

- ^ Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, 8 June 1803,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified April 12, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-40-02-0383.

- ^ Monticello dispersal sale receipts, University of Virginia, MS 5921; Stanton, ‘Those Who Labor for My Happiness,’ 196-8.

- ^ Israel Jefferson, Pike County Republican, 25 Dec. 1873; "ONCE THE SLAVE OF THOMAS JEFFERSON. // The Rev. Mr. Fossett, of Cincinnati, Recalls the Days When Men Came from the Ends of the Earth to Consult `the Sage of Monticello' -- Reminiscences of Jefferson, Lafayette, Madison and Monroe. (Special to the Sunday World.) Cincinnati, Jan. 29. 1898; Virginia Craft Rose, Getting Word interview excerpt, 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=22&v=N6wB60ULO0E.