Contrary to popular belief, the Declaration of Independence was not signed on July 4th, the day it was officially adopted by the Continental Congress.

On the evening of July 4, 1776, a manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence was taken to Philadelphia printer, John Dunlap. By the next morning, finished copies had been printed and delivered to Congress for distribution. The number printed is not known, though it must have been substantial; the broadsides were distributed by members of Congress throughout the Colonies. Post riders were sent out with copies of the Declaration, and General Washington, then in New York, had several brigades of the army drawn up at 6 p.m. on July 9 to hear it read. The Declaration was read from the balcony of the State House in Boston on July 18 but did not reach Georgia until mid-August. Twenty-five original copies of what is referred to as the "Dunlap Broadside" are still in existence.

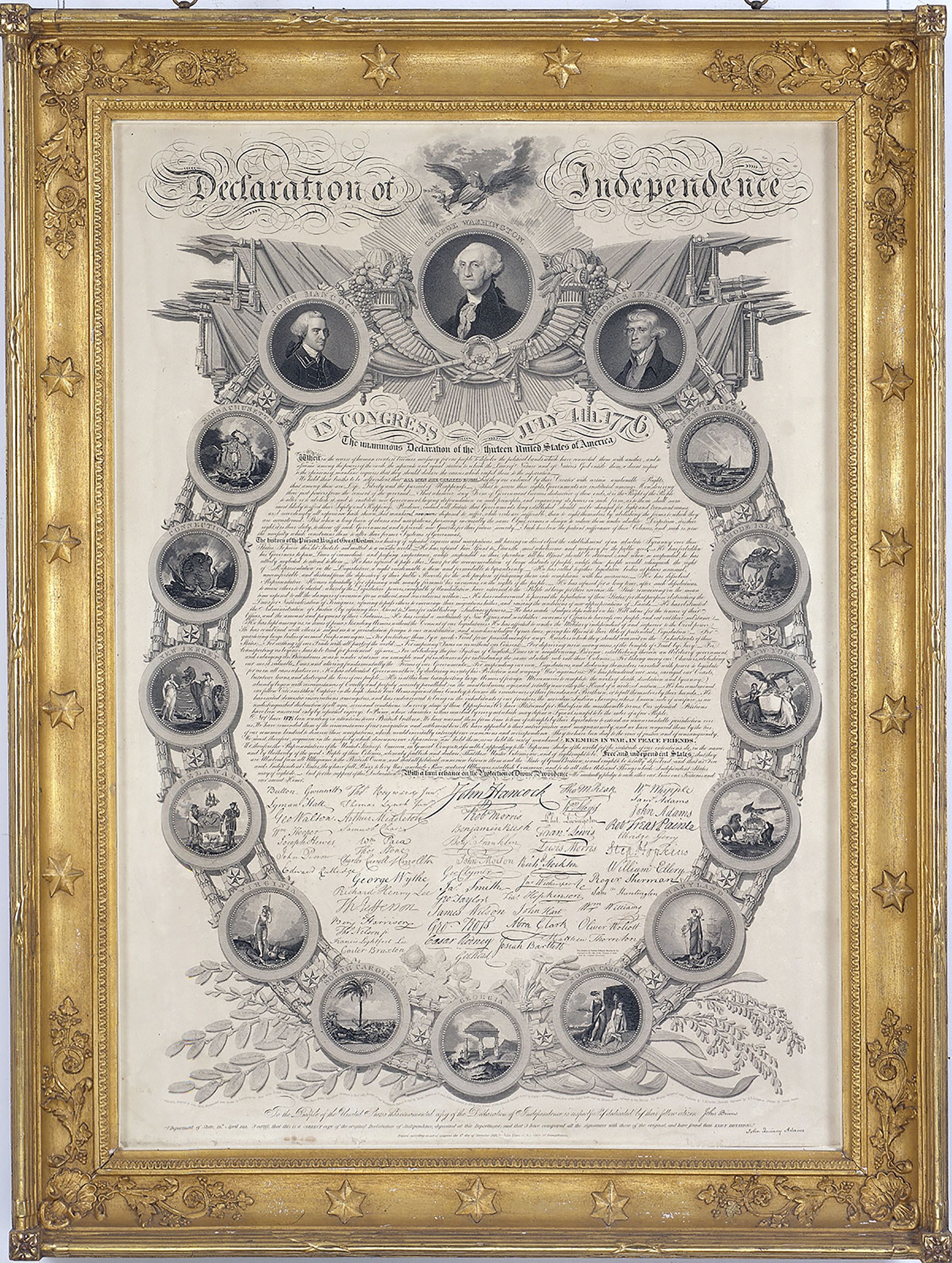

By July 9 all thirteen colonies had signified their approval of the Declaration, and so on July 19 Congress was able to order that the Declaration be "fairly engrossed on parchment. . .and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress." Timothy Matlack is believed to be the person who printed this version of the Declaration. On August 2nd the document was ready, and the journal of the Continental Congress records that "The declaration of Independence being engrossed and compared at the table eas signed."

In time, 56 delegates would sign the “original” engrossed version (including several who had not been present on July 4th).

Following the signing, it is believed that the document accompanied the Continental Congress during the Revolution and remained with government records following the war. During the War of 1812, it was kept at a private residence in Leesburg, Virginia, and during World War II it was housed at Fort Knox. Today, the original document is kept in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.