October 25, 2025

Paper presented at the Archaeological Society of Virginia Conference in Staunton, VA, October 24 - 26

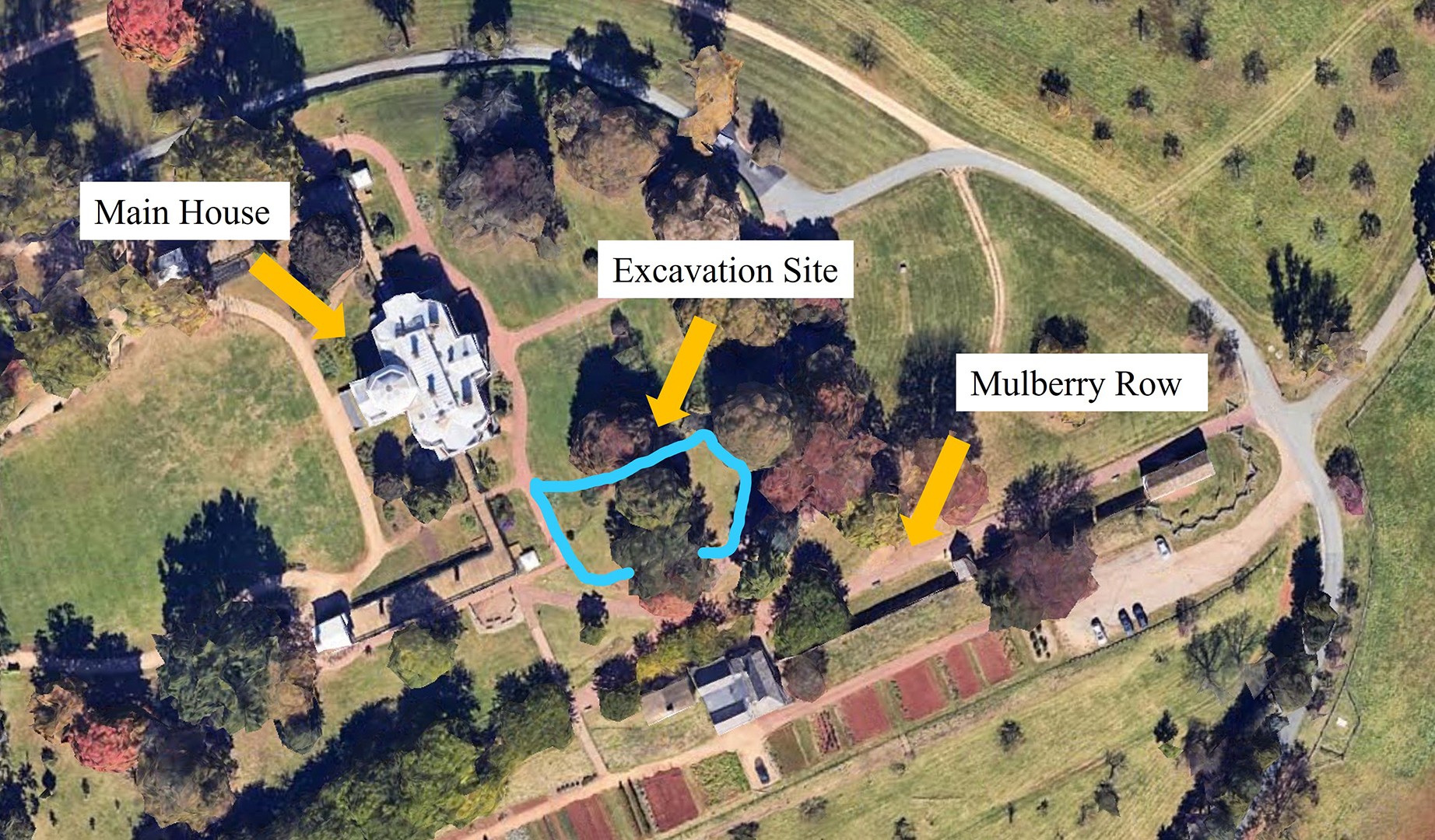

In January of 2025, Monticello’s archaeology department began mitigation excavations ahead of the installation of an ADA compliant pathway on Monticello’s East Lawn. The area of the lawn in question is in the southern portion, directly north of Mulberry Row and south off the axial entrance path to the main house (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Aerial view of Monticello mansion and the East Lawn with the current excavations highlighted in blue.

This area had been subject to archaeological testing before, first during the 2010 Kitchen Road Project, and again as part of Monticello’s Plantation Survey in 2018. Findings from these excavations and documentary evidence suggest that the East Lawn area and the mountaintop as a whole were subject to two large-scale episodes of terraforming performed largely by enslaved laborers, the first during initial construction of the mansion in 1768 and the second during remodeling beginning in the 1790s.

The Monticello Archaeology Department has used this project as a chance to learn about the creation of the current landscape on the mountaintop and to understand the development of that landscape over time. This was alongside secondary goals of investigating for the presence of a Jefferson-era post-and-chain fence in the northernmost part of the project area and interrogating the construction process of a privy vent tunnel built around 1800.

Research Questions

- How was the mountaintop created? How did it change over time?

- Is there evidence for a post-and-chain fence?

- How and when was the privy vent tunnel constructed?

The question of the post and chain was investigated during our annual summer field school, and the area showed no evidence that the fence existed during the Jefferson period. Work on the privy vent only recently came to an end, and it has been determined that fill was removed to construct the feature and then added back in after the construction was done (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Images of the post and chain excavation block (left) and the privy vent excavation block (right) at their completion.

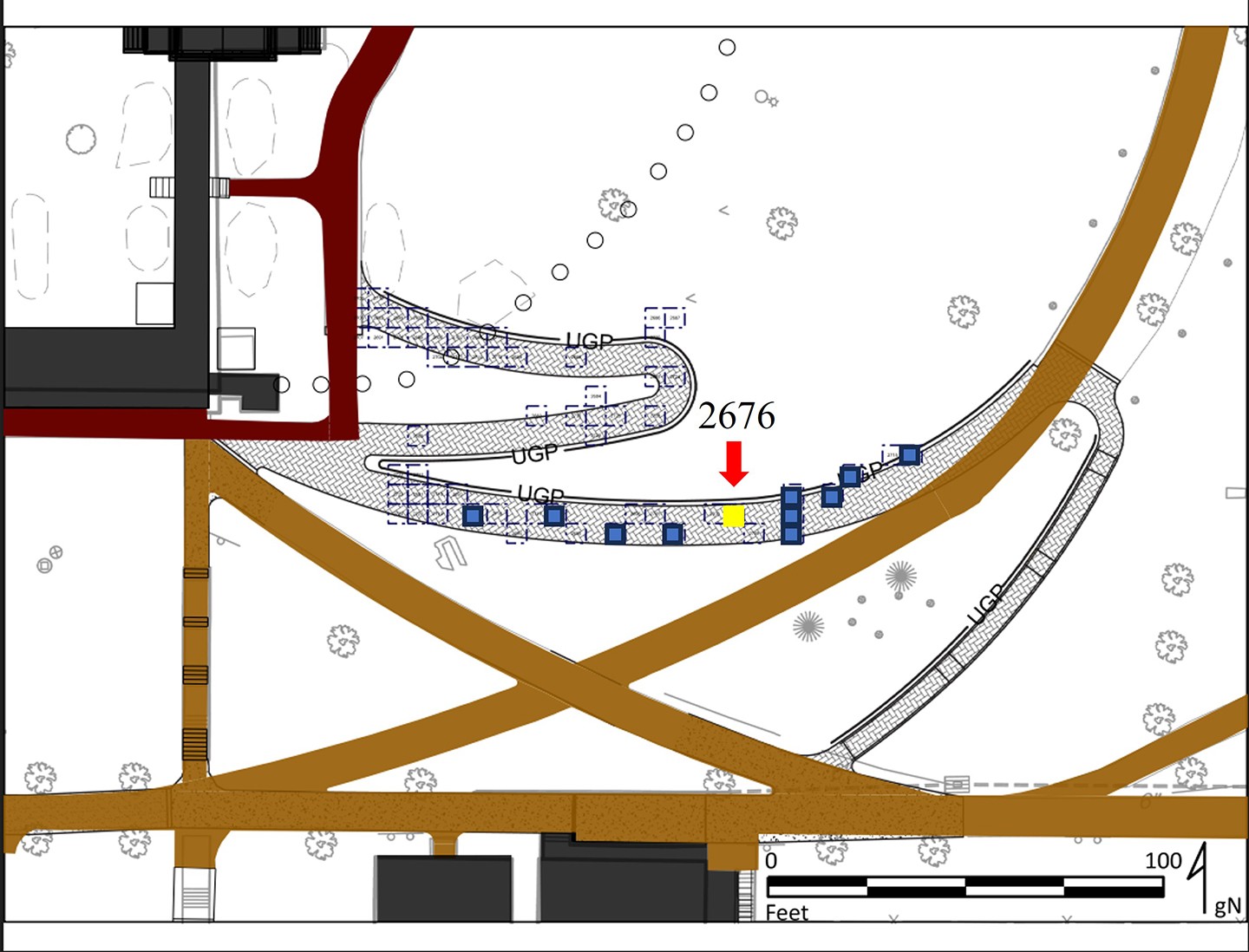

To date, the field crew and field school students have completed 60 5x5 test squares or quadrats in the footprint of the pathway, and the lab team plus volunteers have processed and cataloged 91,860 artifacts, all of which have helped us gain critical insight into a question that only archaeology can really answer. This paper will focus on the first eleven quadrats, 2670-2680, particularly quadrat 2676, which provides a good model to demonstrate site-wide stratigraphic phenomena (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Site map showing the proposed route of the ADA accessibility pathway and quadrats placed along that pathway. The study area for this paper are quadrats highlighted in blue, and quadrat 2676 is highlighted in yellow. Map created by Derek Wheeler.

Though Monticello mountain is the home farm of Thomas Jefferson’s 5,000 acre plantation, Jefferson was neither the first nor the last to occupy the site. Prior to the colonization of the Virginian interior, the territory ranging from the west of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the rivers and floodplains of the Piedmont was held by the Ancestral Monacan people (Wood & Shields 2000). Though we do not currently have evidence for occupation of the mountaintop itself prior to the 1700s, there are Native American sites elsewhere on the property. Artifacts recovered from the Plantation Archaeological Survey have contributed to the identification of at least five archaeological sites on the Monticello Home Farm with pre-contact components, likely representing the activity of Ancestral Monacan people. Incidentally, one of these, Site 30, is currently being explored as an intermittent hunting camp that may have been occupied seasonally (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Examples of projectile points found at Home Farm Quarter Site 30.

By the 1700s, many settlers claimed that the Ancestral Monacan people were absent from central Virginia, though Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia suggests otherwise (Hantman 2018). He described observing a party of Native Americans passing through the plantation on their way to the Monasukapanough burial mound, demonstrating that Monacan people remained connected to their ancestral territory during the 18th century (Jefferson 1785).

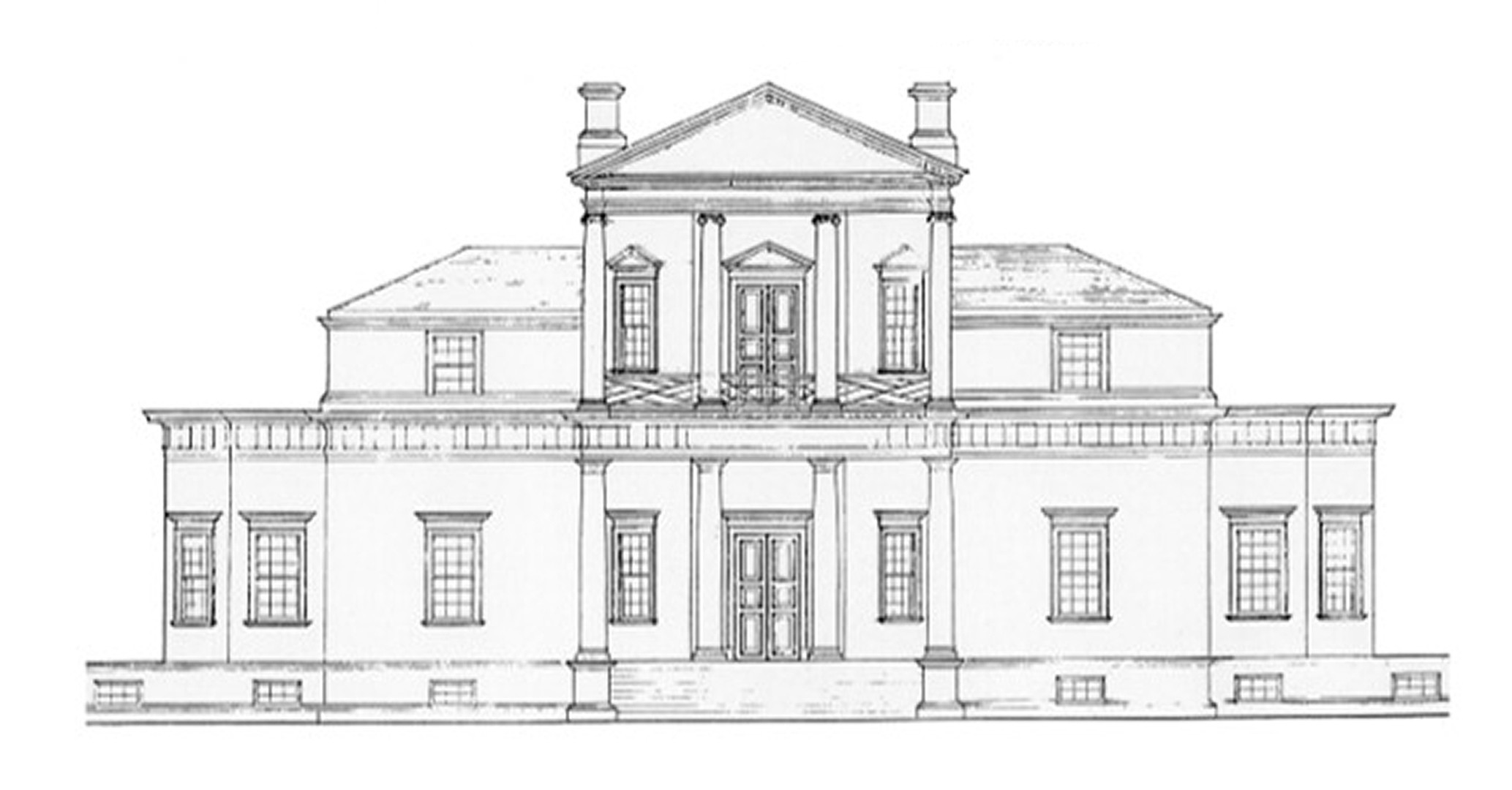

Following the colonization of the Piedmont, Monticello was owned by several families, first acquired by Peter Jefferson in 1735. Thomas Jefferson inherited the Monticello plantation from his father upon his death, and construction of his home on Monticello mountain began in 1768. Jefferson contracted with John Moore, a prominent landowner from Albemarle County, for the initial leveling of a 250 foot square on the mountaintop, upon which the first Monticello would be built by enslaved laborers and free white workmen (Bear and Stanton 1997:76,n2). The first house, with its Palladian architectural program, required roughly 310,000 bricks that were made on site in several batches (McLaughlin 1988). This initial phase of construction included an eight room, double porticoed neoclassical mansion, a well, and several outbuildings (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Drawing of the Monticello I house, which was a product of Jefferson's reading of Palladio.

Jefferson held a number of political offices during this period that called him away from Monticello, including serving as Minister to France. Consequently, he was absent for much of the construction of Monticello I (defined here as 1768-the 1790s), directing and recording from afar through letters exchanged between himself and on-site overseers. When he was present on the mountaintop, he kept meticulous records of the progress of construction and the efficiency of labor.

"Four good fellows, a lad & two girls of abt. 16. each in 8 1/2 hours dug in my cellar of mountain clay a place 3.f.deep, 8 f. wide & 16 1/2 f. long = 14 2/3 cubical yds. under these disadvantages, to wit: a very cold snowy day which obliged them to be very often warming; under a cover of planks, so low, that in about half the work their stroke was not more than 2/3 of a good one..."

Bear and Stanton 1997:36-37

As work on the mountaintop progressed over nearly two decades, Jefferson continually amended his architectural plans, scaling down and adding new features, as shown by ever-changing drawings and maps he made and edited. Despite the decade and a half of work invested, the first iteration of Monticello was likely never fully completed (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Rendering of the landscape of Monticello's mountaintop during the Monticello I era with insets of drawings by Jefferson. Note the changing roadways within the drawings, as well as the presence of service wings, which had not been added to the house yet at the time of either drawing.

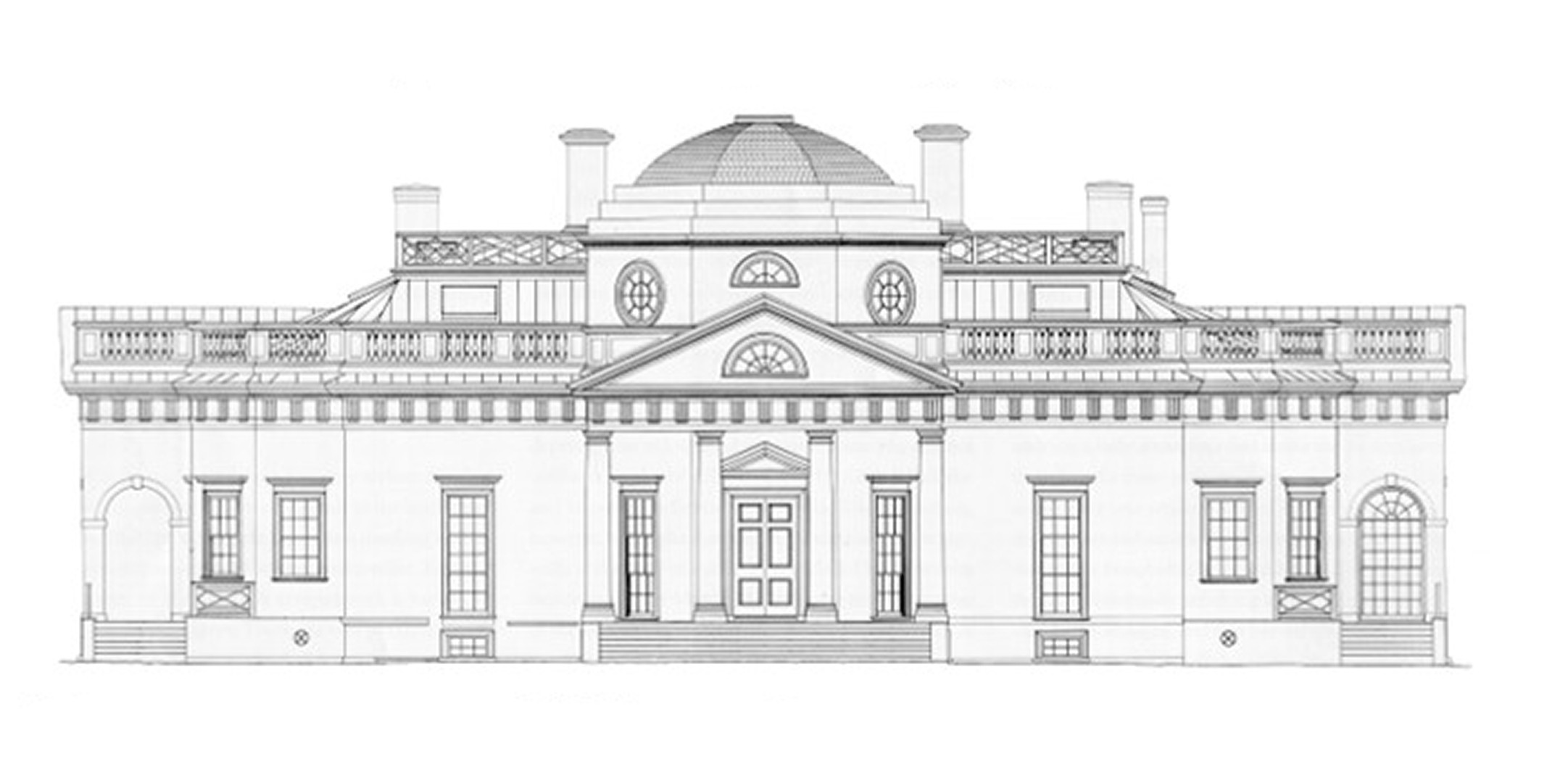

Jefferson returned to Virginia from France in the early 1790s, having been influenced by French neoclassical architecture, and, in 1796, construction began again on a second version of Monticello. As the main cash crop of the plantation transitioned from tobacco to wheat, the house was significantly expanded and took on a more French-influenced architectural style (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Drawing of the Monticello II house, heavily inspired by French architecture.

This process involved the partial demolition of the original structure, the expansion from eight to 21 rooms, and the addition of a number of features including the third story, the all-weather passageways, the service wings, and the dome (McLaughlin 1988) (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Rendering of Monticello II landscape with arrows pointing to the new additions (dome, service wings, and all weather passage).

Additionally, the landscape of the mountaintop was changed during this period, with new access roads being added and additional leveling of the mountain taking place, including further grading of lawns on the east and west fronts of the house. The second and final iteration of the house was completed by 1809, and upon retiring from the Presidency, Jefferson moved back to Monticello for the last time, residing there until his death in 1826.

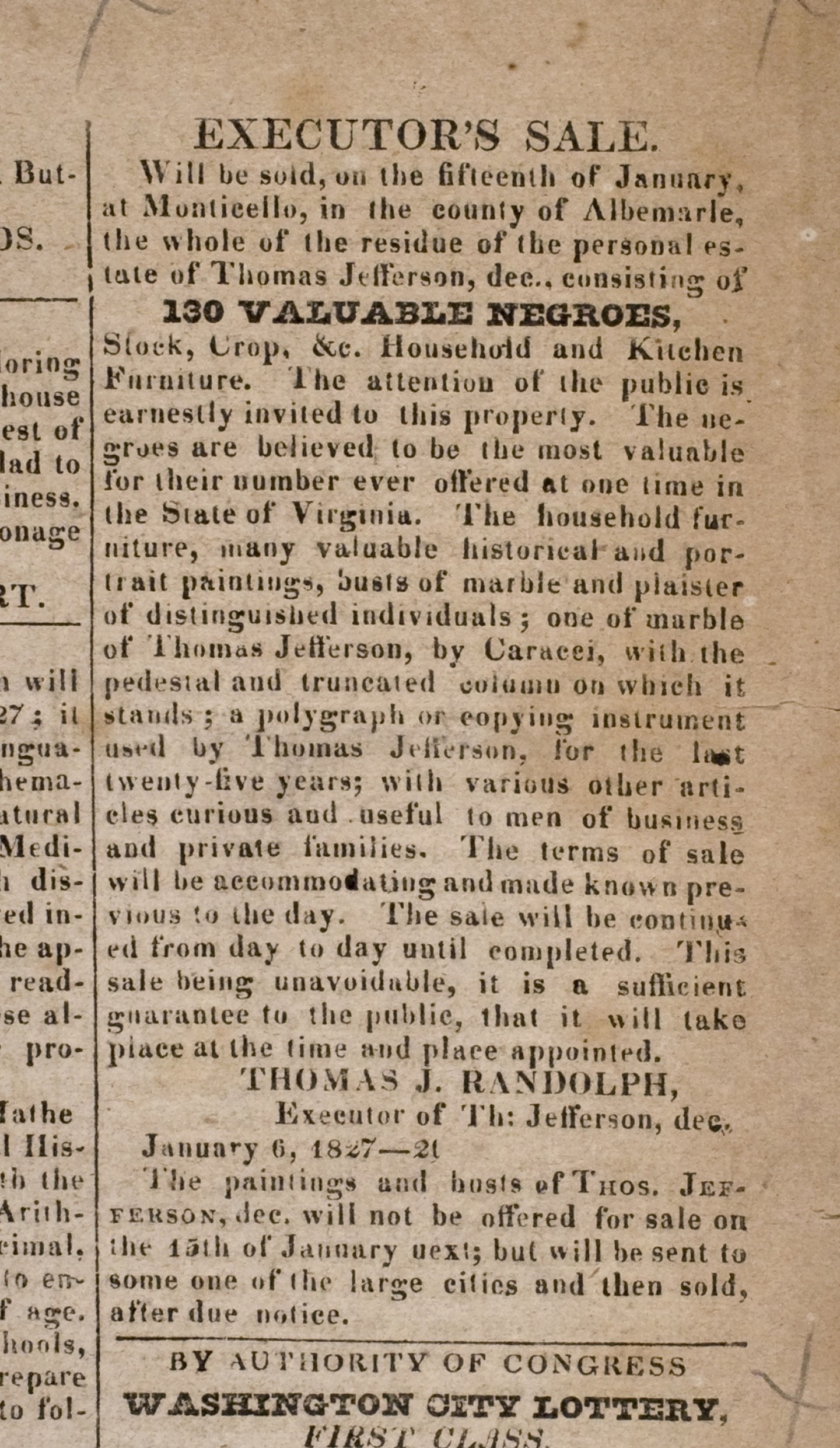

Jefferson left his property to his daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, who also inherited over $100,000 in debt. In 1827, the Randolphs left Monticello, auctioning off furniture, supplies, and equipment in addition to 100 enslaved people who had lived there, and putting the property on the market (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Advertisement in the Charlottesville Central Gazette for the January 15, 1827 Estate Sale at Monticello. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Boston. This was after auction of enslaved individuals and furniture from the house .

It remained empty until 1831, when James Turner Barclay purchased the property, selling it three years later to Uriah Phillips Levy, a Lieutenant for the U.S. Navy (Urofsky 2001). Until his death in 1862, Levy worked to restore and maintain the mansion, save for a brief period when the property was seized by the Confederacy during the Civil War. After a 17-year legal battle over Uriah Levy’s will, his nephew Jefferson Monroe Levy gained the title in 1879 and went on to repair and restore the house and grounds (Leepson 2001). After 89 years of the Levy family’s stewardship of the property, in 1923 Monticello was purchased by the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, now the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. In the ensuing years, there have been numerous construction and restoration projects on the Mountaintop, both by the Foundation and by external organizations such as the Garden Club of Virginia.

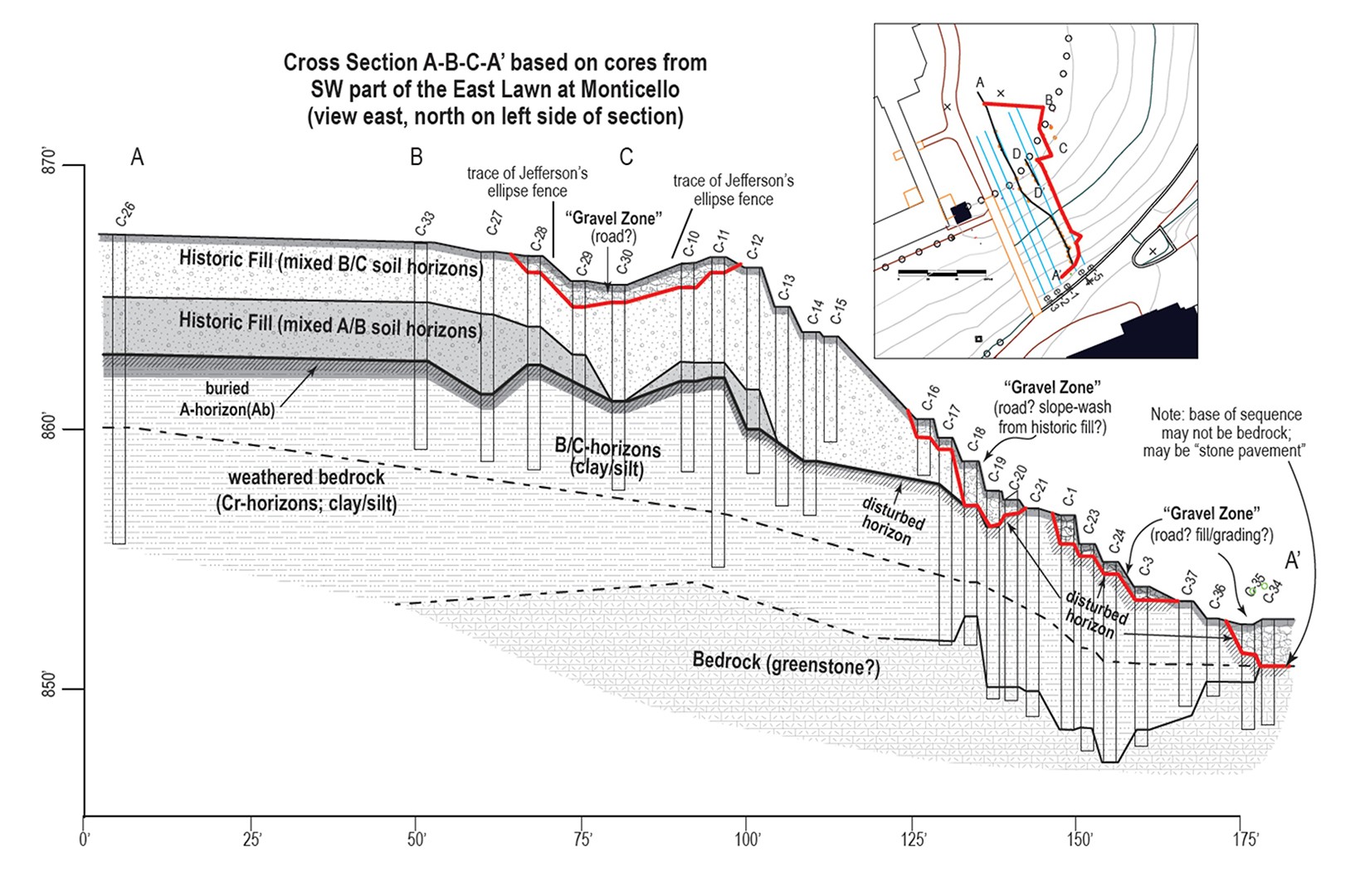

Previous archaeological work on the East Lawn has provided some initial insight into the modifications that took place on the mountaintop. The identification of a buried A horizon has helped us to understand the scale of these modifications. The 2010 Kitchen Road project found this buried A Horizon both within a quadrat and in a series of geoprobe cores taken by Dr. William Monaghan and his team from Indiana University (Figures 10-11).

Figure 10: 2010 Kitchen Road excavations, seeking evidence of a service road between the house and Mulberry Row.

Figure 11: Process of collecting geoprobe cores for stratigraphic analysis.

These cores revealed the presence of a buried A horizon underneath about 5 feet of fill, which was characterized as being a mixed A/B horizon on the bottom and a mixed B/C horizon on top. This project also offered insight into the process of filling itself, noting that the darker, shallower-sourced fills were mostly found in the north of the project area, while the other deeper-sourced fills extended south and east. This indicates that filling likely first took place in the north and west using fill that was sliced off the mountaintop first and moved south and east using deeper sourced B and C fills (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Cross-section diagram of coring results showing the extent of various fill zones (Monaghan 2010).

This coring project also yielded an informative profile from quadrat 2308, which gives a good image of a buried A horizon capped by a mixed B and C horizon fill. Plantation Survey on the East Lawn also was successful in identifying a buried A horizon, this time on the shallower, southern end of the site. This buried A horizon was found at 1.5 feet below ground surface, overlaid by only one layer of redeposited subsoil fill. There were also zones of possible brick firing activity and C horizon dominant fill identified by STPs present to the north of the project area.

The Mountaintop Accessibility East Lawn project set out to further explore and test the conclusions made by this earlier work. 5x5ft quadrats were placed along the projected pathway’s route. The project began by digging quadrats roughly every 15-20 feet to identify deposits, which were interrogated more deeply on subsequent passes. Quadrat 2676 proved to be one of the most clear and representative examples to display preliminary thoughts about the development of the East Lawn landscape and will be used as an example to discuss the stratigraphic phenomena we have been observing, especially in the southern portion of the site. 2676 is located in the southeastern part of the project area and was one of seven quadrats excavated to subsoil in the early part of the project. Beginning in quadrat 2678, the field crew switched to only digging to 1.5 feet, as this is the level at which construction ground disturbance will cease. All sediment excavated was screened through a ¼-inch mesh screen. Sediment layers were then sorted into site-wide stratigraphic groups using Munsell sediment colors and texture descriptions. This is how we were able to characterize each layer and effectively provide MCDs and TPQs in our sample (2670-2680).

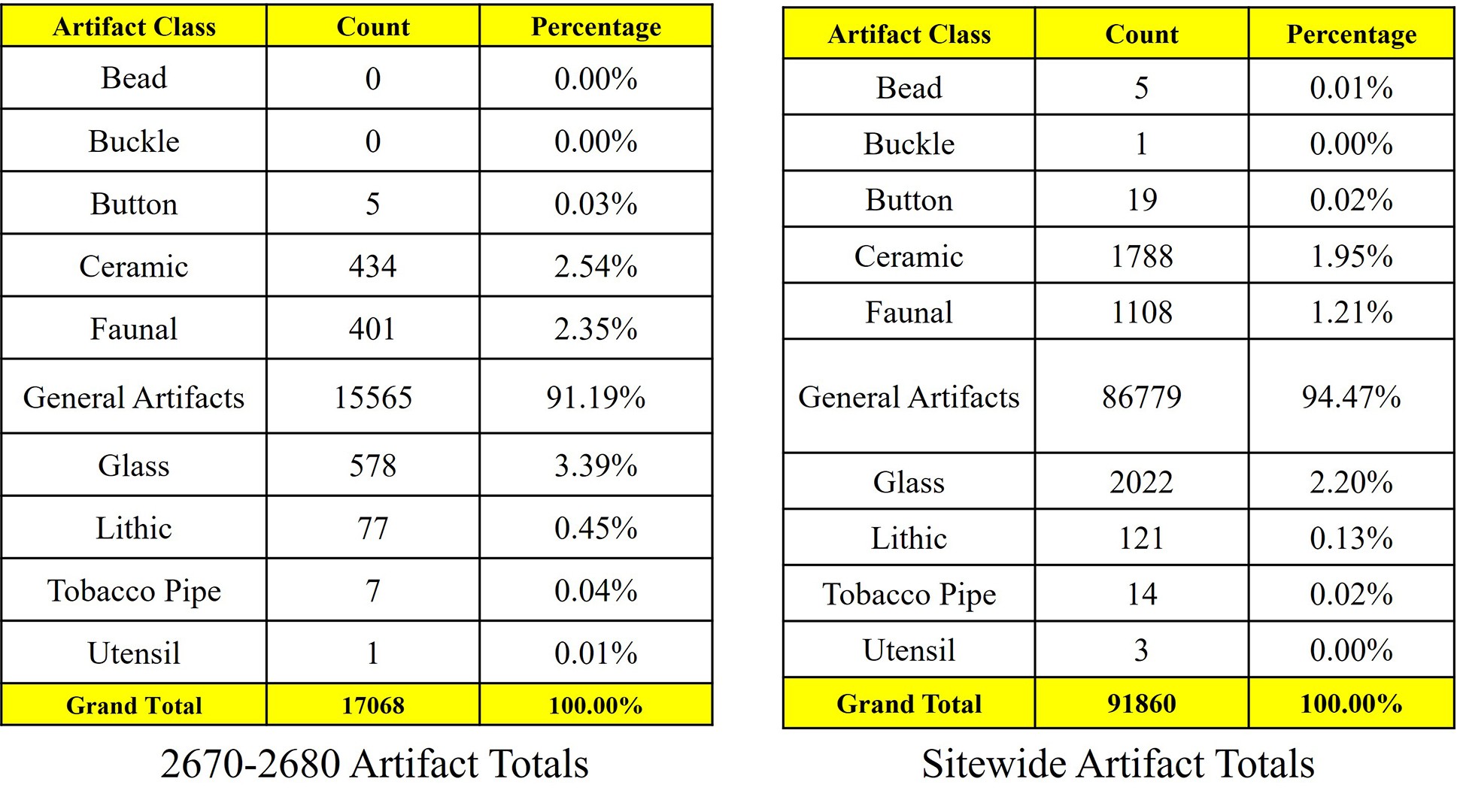

Since the start of the project in January, 91,860 total artifacts have been catalogued using Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery protocols. 17,068 of these artifacts are from the southern portion of the site discussed in this paper (Table 1).

Table 1: Artifact totals from quadrats 2670-2680 (left) and across the site (right).

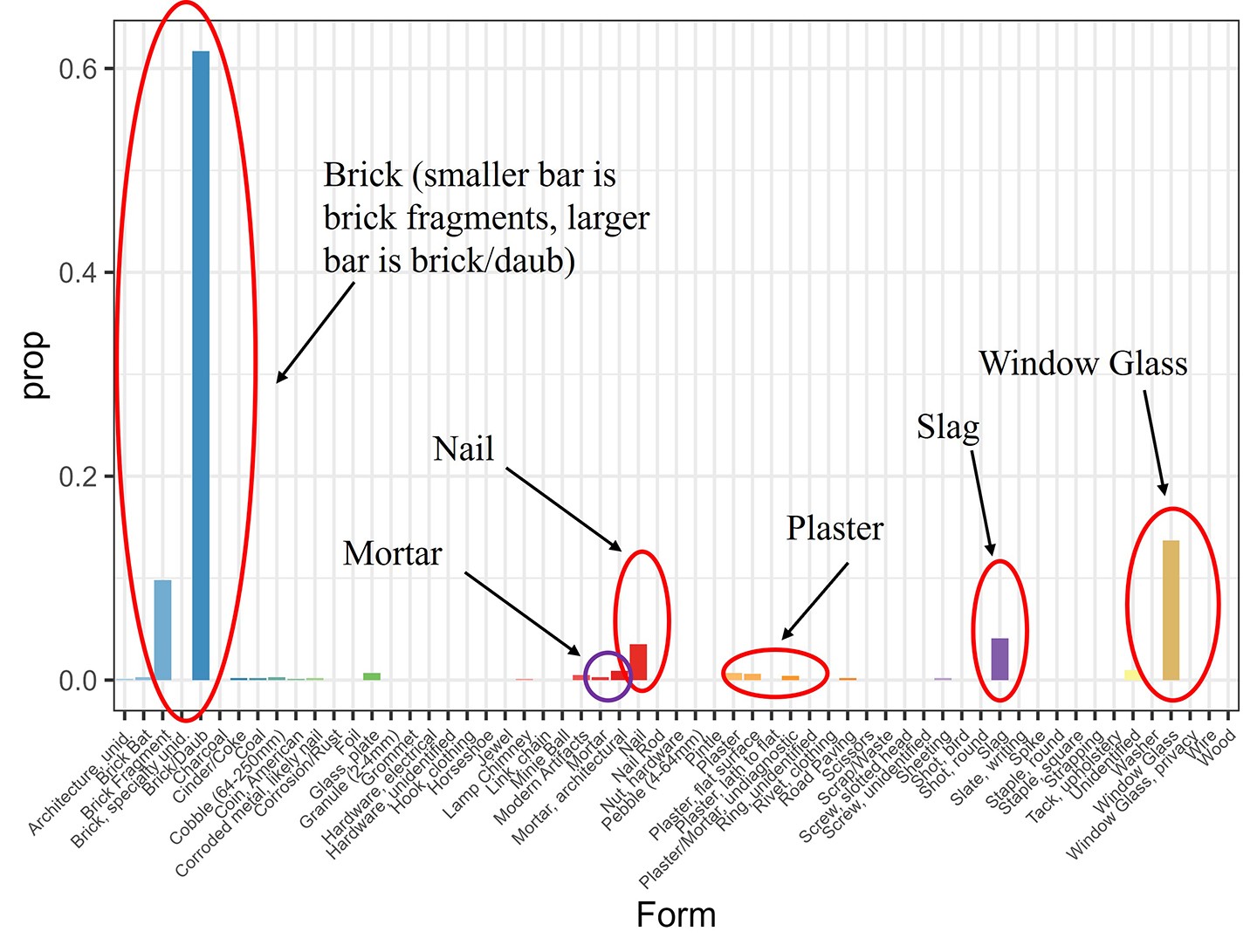

Most of the artifacts processed from the site as a whole at this point are under the category “general artifacts.” The majority of the “general artifacts” from across the site are brick, which comes out of layers from all stratigraphic groups and is by far the most common. The mansion itself is made of handmade brick, and it is likely that brick found was deposited as bricks were broken during construction and deconstruction in the Monticello II era. Other “general artifacts” found in lower quantities across the site are window glass, plaster, mortar, nails, slag, and modern trash, meaning that largely, artifacts found have consisted of architectural material, contributing to the idea that this area was an active construction site for much of Jefferson’s occupancy. In the southern portion of the site, the amount of “general artifacts”, i.e., construction debris, continues to be the vast majority of all artifacts excavated (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Breakdown of the "general artifacts" category with pertinent artifact types indicated.

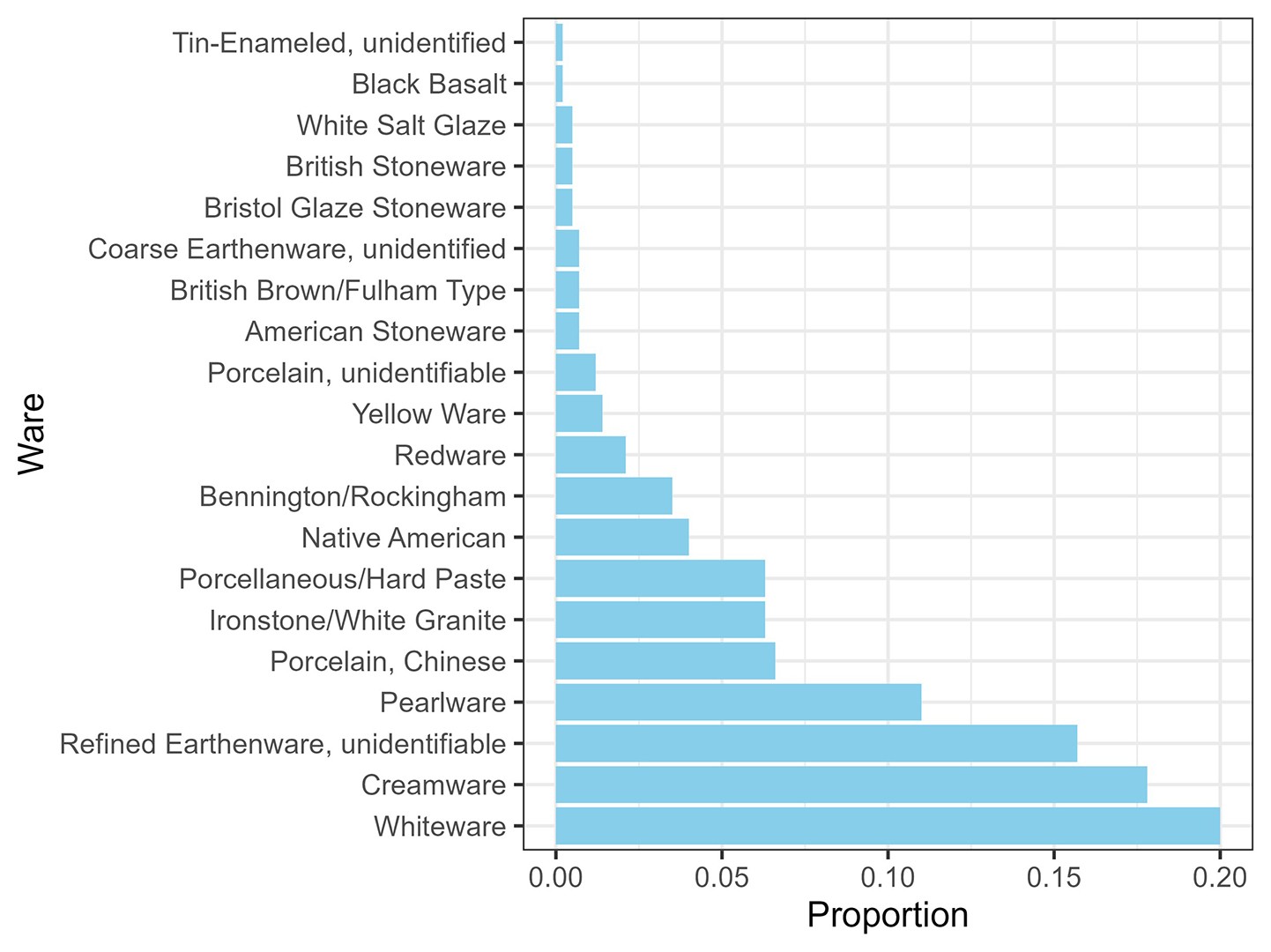

There are also a total of 328 datable ceramics. The types of ceramic present range from Chinese Porcelain and delftware to ironstone and porcellaneous, displaying just how much time is encapsulated within this site (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Ware type breakdown for quadrats 2670-2680.

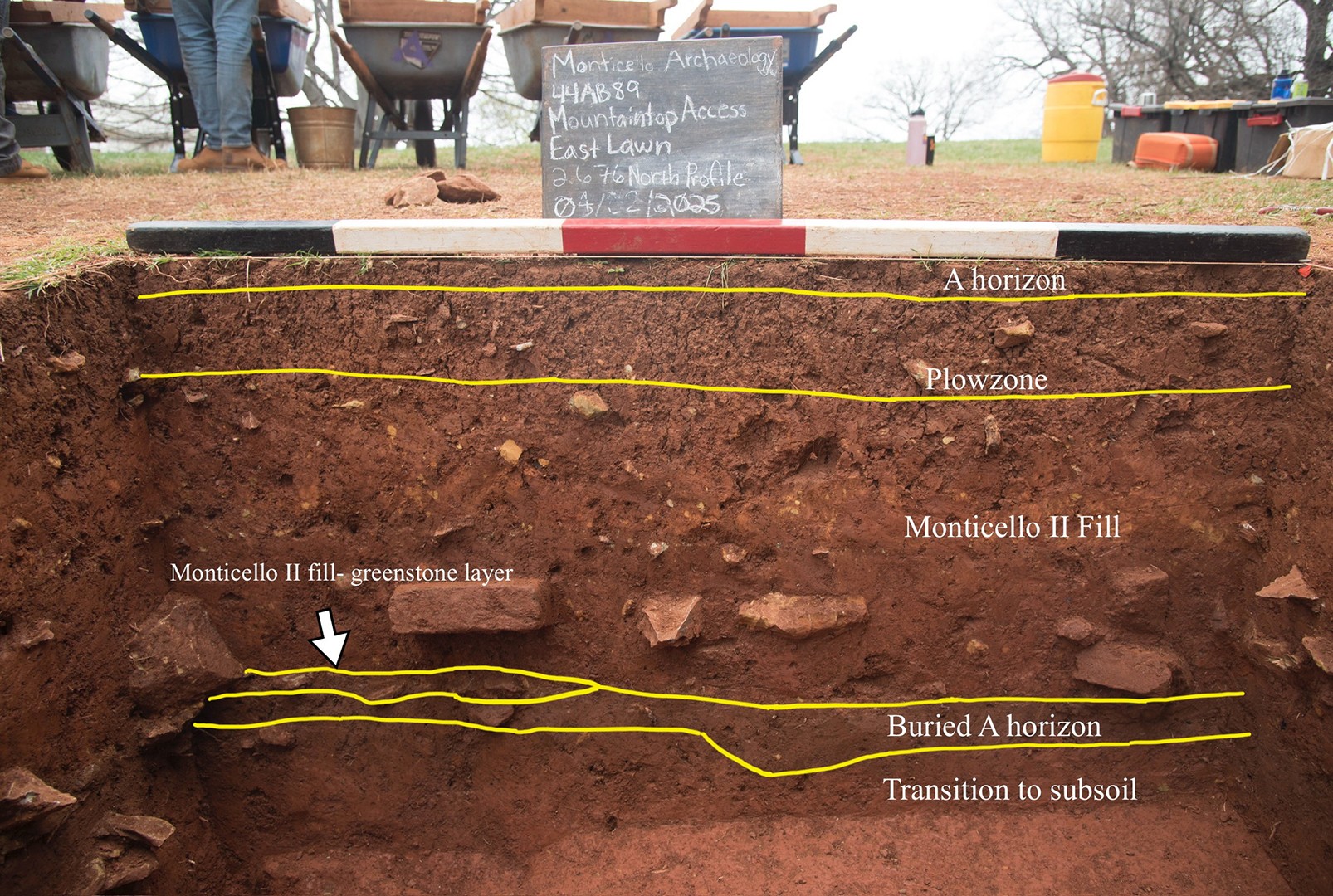

The first stratigraphic layer identified in 2676 is the modern A horizon. This exists across the site and contains artifacts ranging from modern trash to, in some cases, 18th-century material. Below this modern A horizon is a layer of more crumbly, reddish brown sediment, determined to be a plowzone (Figure 15).

Figure 15: North profile of quadrat 2676.

While Jefferson did not have the East Lawn plowed or planted, there are plow scars containing mid-19th century ceramics from excavations along the Inner Loop road just east of our project area to suggest that the Levy family did, and this layer is the result of those activities (Figure 16).

Figure 16: Inner Loop excavations showing visible plow scars, which are circled in red.

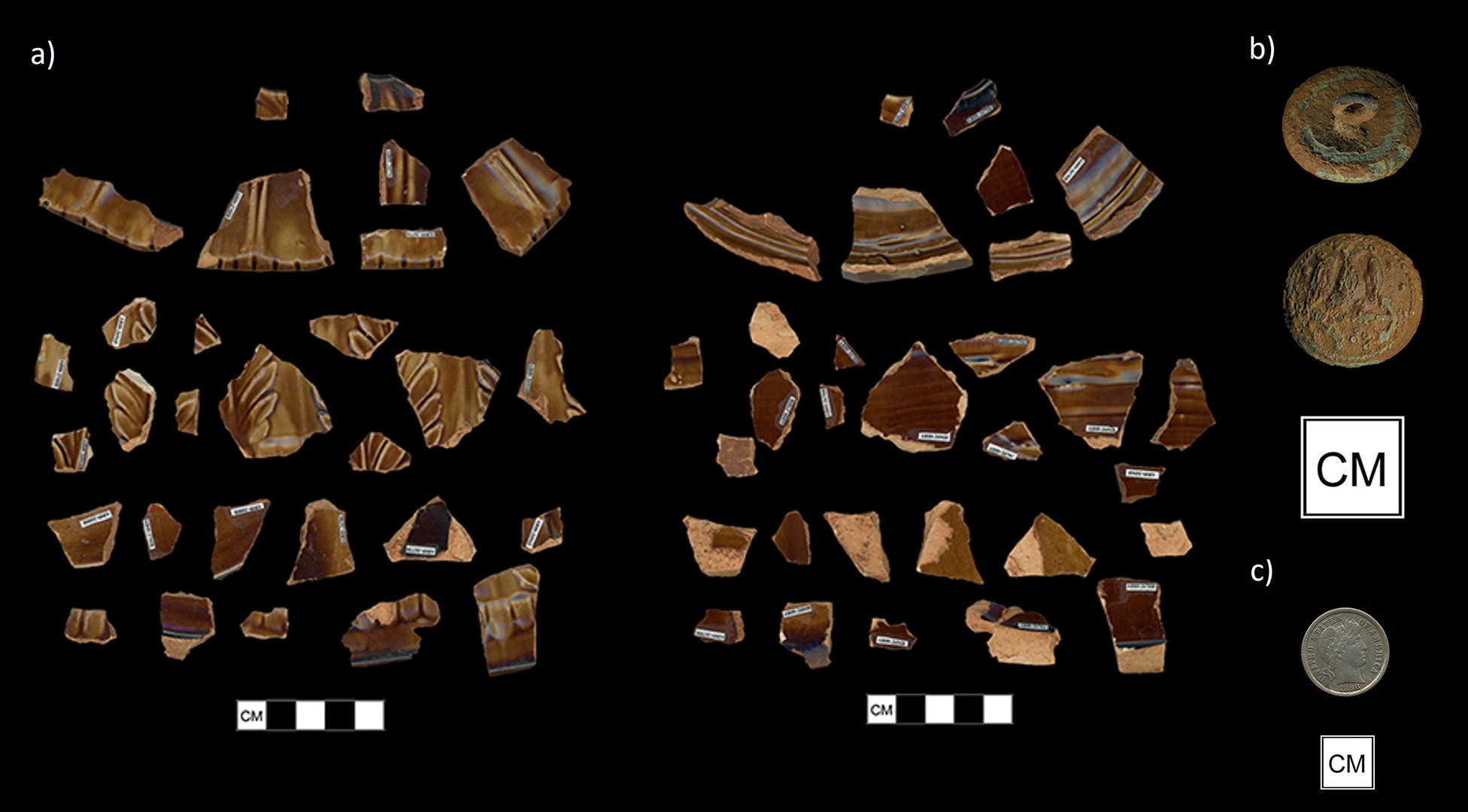

Notably, the plowzone seems to thin out and disappear entirely as one moves north or east; however, it is present in the southeastern portion of the site, where 2676 is located. Artifacts from this layer represent a mix of 19th- and 18th-century material, including post-Jefferson ceramics like ironstone, rockingham/bennington, and whiteware, but also containing earlier-dating ceramics such as white salt-glazed stoneware, Black Basalt, creamware, and pearlware. This layer contained the most datable ceramics with 204 sherds and has an MCD of 1860, a blueMCD (a type of MCD that emphasizes ceramics with tighter date ranges) of 1820, and a TPQ of 1840, meaning that artifacts deposited were largely post-Jefferson, but seems to have some Jefferson-era artifacts mixed in from the plowing. Interestingly, there is a large concentration of mid- to late-19th-century artifacts under an oak tree directly west of 2676, which have potential as a way to archaeologically investigate the lives and materials used by the Levy family and the enslaved laborers and overseers living at Monticello during their tenure as the property owners. This concentration is likely the source of the high density of artifacts within the plowzone, as artifacts from this area were pushed out further into the site as the plow moved along (Figure 17).

Figure 17: Examples of artifacts found in the Levy period deposit on the East Lawn. a) Rockingham/Bennington spittoon with molded botanical decoration and paneled sides. b) Copper alloy U.S. Naval button with eagle/anchor motif. c) 1898 One dime coin.

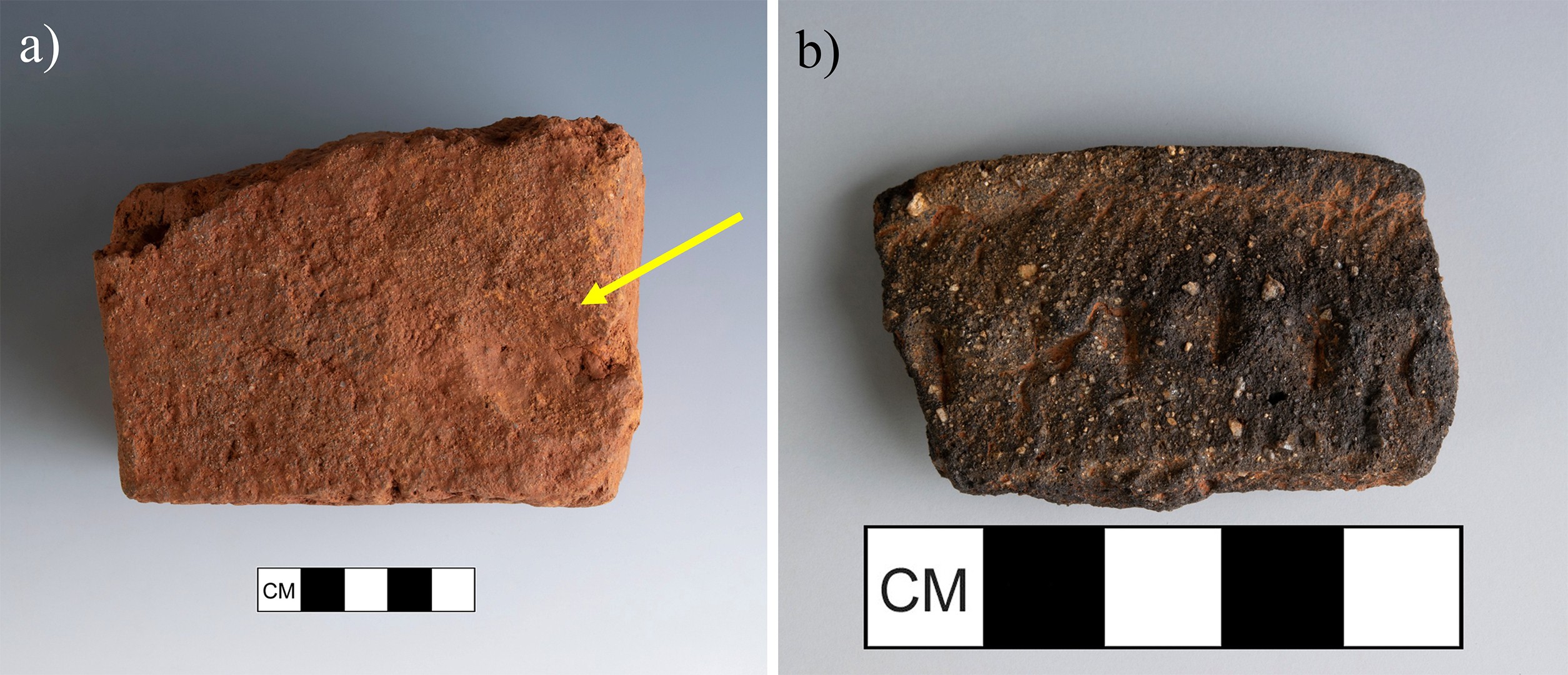

The plowzone seals a more red, consolidated clay layer. This is the fill layer deposited during the construction of the second Monticello mansion, dated to that period in 2676 by a sherd of transfer-printed pearlware. This layer contained a much lower artifact density overall, as well as a much lower occurrence of any domestic materials. Instead, artifacts consist of mostly construction and architectural materials, namely, handmade brick, one piece of which had a fingerprint. Datable ceramics from our sample total 80, which include Chinese porcelain, British stoneware, redware, pearlware, creamware (which was the most ubiquitous in this layer), and, interestingly, Native American pottery (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Artifacts found in the Monticello II fill layer in 2676, including a) brick with a visible fingerprint (shown with the yellow arrow) and b) a highly decorated sherd of Native American pottery.

The presence of the Native pottery suggests Ancestral Monacan sites were disturbed during Monticello II construction and raises interesting questions surrounding the Monacan people’s use of the mountaintop before the mansion was built. The MCD of this deposit is 1804, the blueMCD is 1796, and the TPQ is 1830. The Monticello II fill layer is composed of a redeposited subsoil, which accounts for its consolidation and high clay content. Consistent presence of decomposing greenstone throughout this fill layer suggests that this is likely the mixed C and B horizon fill found by the Indiana University team in 2010. This fill is a constant presence across the site, unlike the plowzone, and only becomes thicker as one moves north up the hill.

Monticello II fill does not just present as a consolidated red clay, and a layer on the west wall of 2676 proves that. Though it is thin, there is a layer beneath the fill that consists of a yellowish-red matrix and heavy concentration of decomposing greenstone. Greenstone is an iron-rich stone which is the bedrock of Monticello Mountain, and as it decomposes, can present as a yellow tinted dust. This deposit of heavy greenstone inclusion is only at its tail end within 2676, presenting at full force 15 feet west in 2677, in which it is not only decomposing greenstone dust but a thick layer of greenstone cobbles and handmade brick bats (Figure 19).

Figure 19: (left) West profile of 2676, showing the greenstone-laden fill layer as it thins out, and (right) a plan view of the rubble deposit as it presented in 2677.

This layer could be a deposit of field stone and waster bricks or bricks removed during deconstruction of the first mansion. There are not many artifacts besides brick in this deposit, but the amount of brick is notably immense. Only 2 sherds of ceramic came out of this deposit within our sample: one piece of American Stoneware and one piece of Native American pottery, meaning there is no reasonable way to provide MCDs, though the American Stoneware gives a TPQ of 1750. This greenstone and brick heavy deposit continues west of 2676, all the way to the westernmost extent of the project area. There are additional layers of decomposing greenstone rich sediments to the north, but at this time, it is unclear if those are the same deposit, as they are less brick-dense. 2676 is the eastern border of this deposit within the project area.

The greenstone-heavy layer in 2676 seals the buried A horizon discovered by STPs and in the Kitchen Road project. This horizon is characterized by a brown soil with some charcoal content and more loamy consistency (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Project Archaeologist Mary Armstrong points to the buried A horizon with her trowel.

To the east of 2676, where there is no greenstone cobble layer, excavators noted that the redeposited subsoil fill feels as though it peels right off to this surface, creating stark contrast. This layer contained very few artifacts. As far as datable ceramics go, there was only a piece of Chinese porcelain and one Native American ceramic found, which leaves no room to generate MCDs and gives a (vague) TPQ of 1600. This layer was sampled in every quadrat in which it was encountered for both floatation and germination. These samples have yet to be processed and analyzed. Under this is a transition to subsoil and a subsoil layer, which is where excavators ceased.

So, what does all of this tell us about the creation of the East Lawn and how it has changed over time? These layers characterize the southern portion of the project area, and reveal something important: there seems to only be fill from the second filling and construction episode in the south. The fill layer present is from Monticello II, a fact which is confirmed by datable ceramics producing a blueMCD of 1796, squarely within the Monticello II era. This further confirms the conclusions that were made during the Kitchen Road project about filling beginning in the north and spreading to the south. This also suggests that during the era of the first mansion, the East Lawn was a much smaller area and did not extend to its modern boundary until construction and filling for the second mansion took place. The fill was not only composed of sediment, but construction debris were also dumped in places in order to bolster the sediment taken from borrow areas. Though the layer of debris does not have as definitive of a date range, it seems unlikely that Jefferson would have had a pile of brick and greenstone debris present in his front yard for the entirety of the Monticello I era, and this is more than likely the construction debris from the beginning of the Monticello II construction process. Even so, the construction process left lots of debris, a fact that is true across the site and especially in the southern portion. The landscape, despite looking natural, was a constantly developing object, taking shape over time and through intense amounts of labor. The profile of 2676 stands as a visual representation of this (Figure 21).

Figure 21: North profile of 2676 displaying the amount of sediment which is fill versus natural soil horizons.

Note the sheer amount of sediment present on top of the buried A horizon, which was all moved by enslaved laborers who were using only farming tools. It is only through archaeological investigation that we can truly understand the scale of this labor and what tangible effects it has had on the landscape.

The Mountaintop Accessibility East Lawn project is still ongoing and still developing new hypotheses and testing our current ones as we move along. We are excited to see what else we can uncover on the mountaintop!

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Monticello Archaeology leadership, including Fraser Neiman, Crystal O'Connor, Corey Sattes, Derek Wheeler. Additional thanks to the Monticello Archaeology lab analysts, Chris Devine, Iris Puryear, and Miranda Leclerc. We also acknowledge our fellow team members a part of the Monticello Archaeology field crew: Lizzie Prow, Jack McFadden, Kyle Koch, Alyssa Baker, Luke Arcement, and Chris Lin. We would also like to thank the Monticello Archaeology volunteers and the 2025 UVA-Monticello Archaeological Field School students for their hard work in excavating and processing these materials.

References

Bear, James A., and Lucia C. Stanton. 1997. Jefferson's Memorandum Books. Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767-1826. 2 Vols. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Hantman, Jeffrey L. 2018. Monacan Millennium: A Collaborative Archaeology and History of a Virginia Indian People. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, VA.

Leepson, Marc. 2001. Saving Monticello: The Levy Family's Epic Quest to Rescue the House that Jefferson Built. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville.

Jefferson, Thomas. 1785. Notes on the State of Virginia. Edited with an introduction and notes by William Peden 1955. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

McLaughlin, Jack. 1988. Jefferson and Monticello: The Biography of a Builder. Henry Holt and Company, New York.

Monaghan, G. William. 2010. The Kitchen Road Project: Geoarchaeological Research on the Historic Landscape at Monticello. Report available in Monticello Department of Archaeology, Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Urofsky, Melvin I., and Thomas Jefferson Foundation. 2001. Fall Dinner at Monticello, November 2, 2001, in Memory of Thomas Jefferson. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Charlottesville

Wood, Karenne, and Dianne Shields. 2000. The Monacan Indians: Our Story. The Monacan Indian Nation, Amherst, VA.