The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: A Look at Penmanship

Here at the Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series, we spend most of our days reading Jefferson’s two-hundred-year-old mail. Jefferson wrote approximately 19,000 letters during his lifetime, so you can imagine how many more letters he also received! And that means we have a lot of different handwriting to navigate.

Jefferson’s hand is relatively easy to read, especially once you’ve spent some time with it. He didn’t like to capitalize the beginnings of sentences, and he maintained his own spellings for a few choice words (like “knolege” or “recieve”). But overall his writing is very legible. When Jefferson wrote to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph on 16 April 1810 to encourage him to practice daily letter-writing, he added some advice on penmanship:

“take pains at the same time to write a neat round, plain hand, and you will find it a great convenience through life to write a small & compact hand as well as a fair & legible one.”

Jefferson maintained this “neat round, plain hand,” and I like to call it Good. Or at least really decent. See?

The Good

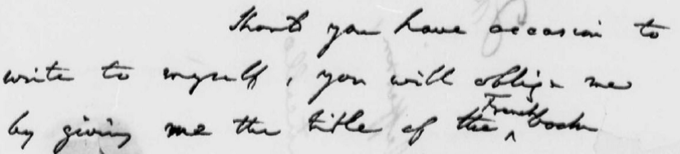

But plenty of people were not so careful with their handwriting. Take this excerpt of Bad penmanship for example:

The Bad

Occasionally we come across a hand that is truly Ugly, such as this:

The Ugly

Any idea who penned that abomination? Well I’ll tell you. It was our esteemed fifth president, Mr. James Monroe. His handwriting was so ugly, in fact, that Jefferson’s overseer Edmund Bacon once said “Mr. Jefferson and Mr. Madison both wrote a plain, beautiful hand, but you could write better with your toes than Mr. Monroe wrote.”*

And this is where the staff of the Jefferson Papers comes in. We read the original scribbles and scrawls so you don’t have to. We understand that many people often feel like Jefferson did in 1816, when a man named Horatio G. Spafford tried to get him to read a handwritten paper that Spafford hoped to publish. In his letter to Spafford of 10 January 1816, Jefferson declined to read the manuscript and instead explained:

“so few are my spare moments that I have not been able even to read it through: because the MS. [manuscript] is in a handwriting extremely difficult to me; and I shall read it with more pleasure, and more understandingly in print.”

As documentary editors, we gather up letters both to and from Jefferson, transcribe the handwriting (good, bad, or ugly), and provide helpful annotation. Then our work is published so everyone can read Jefferson’s mail, too. (There are eight volumes out already, run to a research library and see for yourself!) Our ultimate goal in all of this? We simply strive to preserve Jefferson’s writings in print and to help others read them “with more pleasure, and more understandingly.”

____________________________________________________

*Images of handwriting specimens are taken from Thomas Jefferson to William Duane, 28 Mar. 1811 (“pound is of little concern with them. the last hope of human liberty in this world rests on us. we ought, for so dear a stake, to sacrifice every attachment & every enmity. leave the President free to chuse his own co-adjutors, to”); Benjamin Vaughan to Jefferson, 16 Apr. 1819 (“Should you have occasion to write to myself, you will oblige me by giving me the title of the French book”); and James Monroe to Jefferson, 24 Dec. 1810 (“business of the assembly with much harmony, and there does not appear at this moment to be in any one a disposition to interrupt it. In my judgment the true course is to”), respectively. All are located at the Library of Congress. The quote by Edmund Bacon is in Hamilton W. Pierson, Jefferson at Monticello (New York, 1862), 121-2.