Jefferson's Monticello garden was a Revolutionary American garden. One wonders if anyone else had ever before assembled such a collection of vegetable novelties, culled from virtually every western culture known at the time, then disseminated by Jefferson with the persistence of a religious reformer, a seedy evangelist. Here grew the earth's melting pot of immigrant vegetables: an Ellis Island of introductions, the whole world of hardy economic plants: 330 varieties of eighty-nine species of vegetables and herbs, 170 varieties of the finest fruit varieties known at the time. The Jefferson legacy supporting small farmers, vegetable cuisine, and sustainable agriculture is poignantly topical today.

Thomas Jefferson's 1,000-foot-long, terraced vegetable garden is the true American garden: practical, expansive, casual, diverse, wrought from a world of edible immigrants. Although the variable continental climate of Virginia presents unique horticultural challenges, few places on earth combine tropical heat and humidity with mildly temperate winters like those at Monticello. The microclimate, and really the genius, of the south-facing, terraced Monticello garden exaggerates the summer warmth, tempers the winter cold, and captures an abundant wealth of crop-ripening sunshine. To grow so many tropical species like sweet potatoes, peanuts, and lima beans in the same garden as traditional cool-weather crops like cauliflower, endive, and celery, without artificial hot beds, had likely never been done before Thomas Jefferson accomplished this feat at Monticello.

panorama.

Aside from its diverse population of mostly introduced crops, the Monticello garden was American in its size and scope, experimental character, and expansive visual sweep. 600,000 cubic feet of Piedmont red clay was moved with a cart and mule to create the "hanging garden," and the terrace was supported by a rock wall as tall as fifteen feet and also running 1,000 feet. Below is the six-acre fruit garden that contained 170 varieties of the most celebrated varieties known at the time. As it stretches to the western horizon, seemingly limitlessly against the background of Montalto, Jefferson's "high mountain" to the southwest, or as one looks across the garden terrace to the forty miles of rolling Piedmont, the "sea view," one is struck by the garden's uniquely continental panorama.

Thomas Jefferson liked to eat vegetables—which he said "constitute my principal diet"—and his role in linking the garden with the kitchen into a cuisine defined as "half French, half Virginian" was a pioneering concept in the history of American food. The Monticello kitchen, as well as the table at the President's House in Washington, expressed a seething broil of new, culinary traditions based on these recent garden introductions: French fries, peanuts, Johnny-cakes, gumbo, mashed potatoes, sweet potato pudding, sesame seed oil, fried eggplant, perhaps such American icons as potato chips, tomato catsup, and pumpkin pie. The western traditions of gardening—in England, France, Spain, the Mediterranean—were blended into a dynamic and unique Monticello cookery through the influence of emerging colonial European, native American, slave, Creole and southwestern vegetables.

Jefferson's daughter, Martha, left a recipe for okra soup, in effect, gumbo, a compelling metaphor for the Monticello garden: a rich blend of American native vegetables grown by American Indians like lima beans and cymlins; South and Central American discoveries adapted by both northern (potatoes) and southern (tomatoes) Europeans; and tied together by an African plant, okra, grown by both the French and enslaved blacks in the West Indies, rarely known among white Virginians, and prepared by African-American chefs at Monticello.

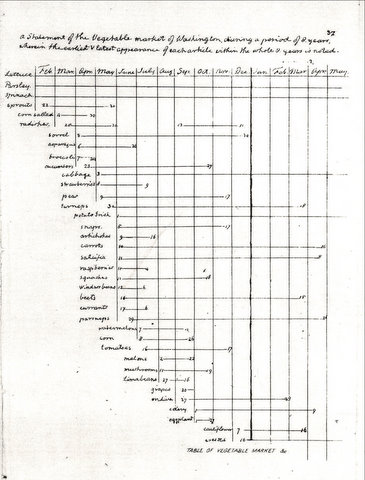

Jefferson, according to culinary historian Karen Hess, was "our most illustrious epicure, in fact, our only epicurean President," and his devotion to fresh produce, whether in the President's House at a state dinner, or at Monticello for the large numbers of celebrity tourists who crowded the retired President's table, remains a central legacy of Jefferson's gardening career. Jefferson also promoted commercial market gardening. The remarkable calendar he compiled while President, delineating the first and last appearance of thirty-seven vegetables in the Washington DC farmer's market, is among the most revelatory documents in the history of American food. As well, it was Jefferson himself who obtained new vegetable varieties from foreign consuls, passed them on to Washington market gardeners, and ordered his maitre'd to pay the highest prices for the earliest produce.

In 1792 Jefferson, while serving as Secretary of State in Philadelphia, received a letter from his daughter, Martha, complaining about the insect-riddled plants in the Monticello Vegetable Garden. His response is a stirring anthem to the organic gardening movement. "We will try this winter to cover our garden with a heavy coating of manure. When is rich it bids defiance to droughts, yields in abundance, and of the best quality. I suspect that the insect which have harassed you have been encouraged by the feebleness of your plants; and that has been produced by the lean state of the soil." Jefferson's rallying cry on the remedial value of manure, the horticultural rewards of soil improvement, has inspired gardeners of all kinds. Jefferson not only enjoyed the garden process and relished eating fresh produce, but the garden also functioned as an experimental laboratory, in some ways, as a vehicle for social change. He wrote that, "the greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add an useful plant to its culture," and Jefferson ranked the introduction of the olive tree and upland rice into the United States with his authorship of the Declaration of Independence. A Johnny Apple seed of the vegetable world, Jefferson passed out seeds of his latest novelty with messiahinistic fervor: not only to friends and neighbors like George Divers and John Hartwell Cocke, his family of daughters, granddaughters, and sons in law, but to fellow politicians—from George Washington to James Madison—and the leading plantsmen of the early nineteenth century like McMahon, William Bartram, William Hamilton of Philadelphia, and André Thouin of Paris. Although few species can be proven as Jefferson introductions into American gardens, the recitation of vegetables grown at Monticello is a meditative chant of rare, unusual, and pioneering species: asparagus bean, sea kale, tomatoes, rutabaga, lima beans, okra, potato pumpkins, winter melons, tree onion, peanuts, "sprout kale," serpentine cucumbers, cauliflower, broccoli, Brussells sprouts, orach, endive, chick peas, cayenne pepper, "esculent Rhubarb," black salsify, sesame, eggplant.

Although a modest endeavor, Jefferson's only published horticultural work was "A General Gardening Calendar," a monthly guide to kitchen gardening that appeared in a May 21, 1824 edition of the American Farmer, a Baltimore periodical of progressive agriculture. Here Jefferson authoritatively instructed gardeners to plant a thimble spool of lettuce seed every Monday morning from February 1 to September 1, as if the Monday morning lettuce sowing was a life lesson or discipline akin to dutifully saying your prayers or cleaning one's dinner plate; the rites of Monday morning led to a long life, happiness, and good teeth.

Michelle Obama recently declared that the White House kitchen garden "has been one of the greatest things I've done in my life so far." An admirer of Thomas Jefferson and inspired by a visit to the Monticello garden, White House chef and Coordinator of the White House Food Initiative, Sam Kass, reserved a discrete section of this garden in honor of Thomas Jefferson. In the spring of 2009 it was planted with seeds and plants of Thomas Jefferson's favorite vegetable varieties: Tennis-ball and Brown Dutch lettuce, Prickly-seeded spinach and Marseilles fig. The Jefferson legacy in gardening and food is not a mere historical curiosity, but is a compelling force in the movement toward a more sustainable agricultural future.